People and the Derwent: A Modern River’s Life Cycle

From its source in a Lakeland tarn to the Irish Sea, this piece traces the route of the Lake District’s River Derwent and the people it encounters on its way.

Originally written for retailer George Fisher and brand Patagonia, this piece was first published on the George Fisher website as part of a wider content campaign.

If water, nature’s greatest sculptor, named its masterpieces, the Lake District would surely fall somewhere near the top. Not just for the sixteen large bodies of water that give our National Park its name, but for its wide, glacial valleys and the aged faces of its crags. But between the broad brushstrokes of thousands of years worth of water-powered weathering, there are less-obvious wonders, ecosystems still being sustained that are just as breathtaking and much more fragile. Water still has plenty of work to do here in The Lakes.

Luckily, we don’t half get a lot of it. Rain that is. In fact, Seathwaite, at the heart of Borrowdale, famously holds a record. Storms generated in the subtropical Atlantic get their first taste of the northern European landmass when they collide with the Cumbrian mountains populating this most north-westerly of England’s corners. As a result, as much as 5000mm of rain pelts Borrowdale’s valley sides and fells over the course of a year, more than anywhere else in the country.

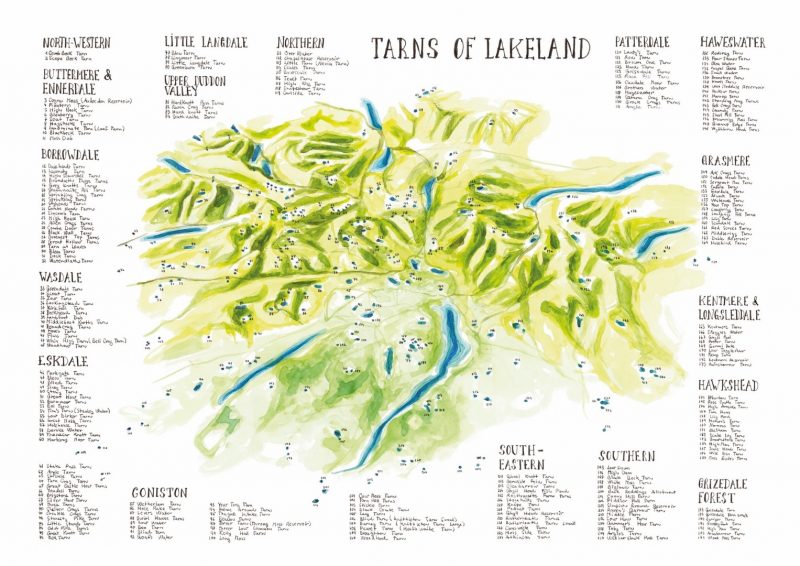

Just a few kilometres south of Seathwaite, at the foot of the most towering of Borrowdale fells, you’ll find the onomatopoeic Sprinkling Tarn and its sister tarn, Styhead. At over 2000ft, these cold, fresh waters are fed by the runoff of this record-breaking weather. But while giants like Great End, Great Gable, and Scafell Pike all surround this wilderness, it’s anything but barren. From here, high in Lakeland’s hills, a short but meaningful journey begins. Wordsworth’s ‘tempting playmate’, the River Derwent is starting its 25 mile march to the Irish Sea.

Even while not much more than a trickle, the young river is a lifeline in its valley. As it rolls into Borrowdale, it feeds a landscape declared a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) by the European Commission. An impressive selection of rare plants, animals, and habitats have been identified here and the River Derwent and its tributaries lie at their centre.

If you’re lucky, you’ll spot the Touch-me-not Balsam and Alpine Enchanter’s Nightshade growing in patches of bracken or shading in the most extensive block of old sessile oak woods in northern England. In fact, it’s these oaks that are responsible for Derwent’s ancient name, Derventio: the Celtic word for a valley thick with oaks. Amongst these, areas of rare peat bogland dot the woods where you can glimpse a flutter of a threatened Marsh Fritillary Butterfly. Along the riverbank, you might even catch the chatter of otters or the splash of a spawning Atlantic salmon. If you’re lucky, that is.

Sadly today, habitats like this are increasingly precious. Climate change, farming, and human intervention threaten these ecosystems making it more important than ever that they’re managed and protected by dedicated and knowledgeable organisations. For the River Derwent’s catchment, this responsibility has been taken up by the West Cumbrian Rivers Trust. Relying on grants, like Patagonia’s World Trout Fund, as well as support from dedicated volunteers, they do the work that helps the river survive in a modern world.

Subscribe to our newsletter

This isn’t always easy. They state over 50% of the rivers and streams in the Derwent’s catchment are in an unfavourable condition with problems ranging from artificially straightened stretches of river to widespread deforestation of floodplains, often resulting in declining native wildlife. As a result, the work they take on is extensive and varied. Tree-planting and reintroducing meanders in the floodplain works to prevent flooding further downstream at places like Cockermouth. Surveys conducted at over 150 sites along the river help build an understanding of fish numbers, their environment, and the impact of increasingly frequent extreme weather.

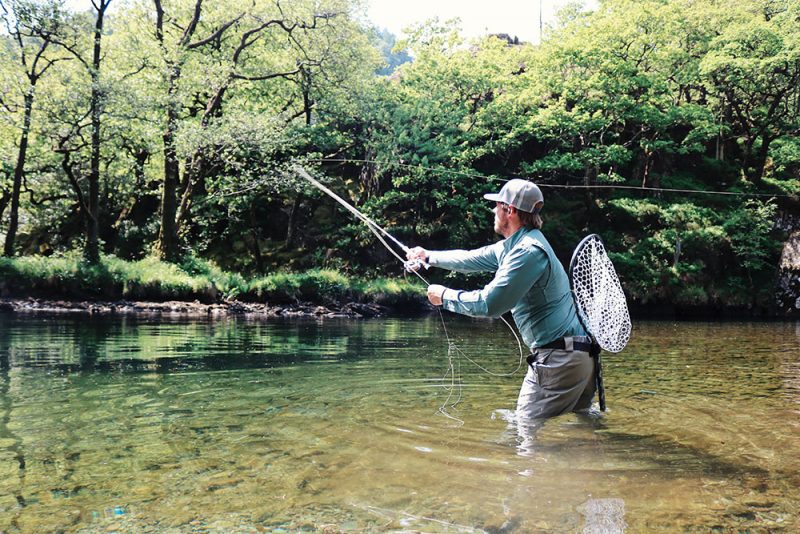

More often than not, at the heart of these conservation efforts are people who are driven to help by their passion – anglers and flyfishers. As the river meanders and slows towards Derwentwater, it offers them, for their hard work, a different kind of sustenance: escape. Waist deep in the Derwent, the slow rhythm of casting and the silent waits in between provide a connection to the wild that exist entirely outside of any instantly-gratifying digital world. The river gives the flyfisher the moments of clarity, excitement, and adventure that are craved more than ever. In return, it gains the people it now so sorely needs fighting its corner.

“The thought of losing our home run made us look a little deeper into what our connection with our local rivers actually is.”

This reciprocal relationship isn’t limited to the more peaceful of water pursuits, either. “We came into river conservation through whitewater kayaking,” says Dan Yates of river conservation organisation, Save Our Rivers. In the rapids of another British river, North Wales’ Afon Conwy, Dan discovered his calling was protecting these environments. Supported by 1% for the Planet – a grant funded from 1% of the profits of businesses including Patagonia – he headed up a campaign that successfully took on and halted a plan to dam and divert his beloved Welsh river, a project that would have been disastrous for the habitats that exist there.

“I think from that initial connection of having fun and paddling rapids, we could see how terrible it would be to lose the places that mean so much to us.” Dan continued, describing how Kayaking acted as a gateway to understanding the importance of river environments. “The thought of losing our home run made us look a little deeper into what our connection with our local rivers actually is: we soon realized that we had a profound attachment to the place, not just the activity.”

As it passes to the west of Lodore Falls, eight miles from its source, the River Derwent meets Derwentwater, the third largest body of water in the Lake District. Here, people and the river’s waters are pushed together on a daily basis. Like many of its Cumbrian counterparts, Derwentwater dominates the community around it, not just the landscape. It’s lakeside is home to Keswick and its theatre and parks. Its waters carry the canoes of locals on their afternoons off and the steady flow of boats of tourists on their adventures across the lake. Do we still have things to learn about the wildlife of a water so well-paddled?

“Not many people have heard of the vendace,” says Sam, a third year conservation student at the University of Cumbria who specialises in one of Derwentwater’s lesser-known inhabitants. “That’s part of the reason it’s classified as Britain’s rarest fish,” he told us. In fact, the two populations in the Lake District – at Derwentwater and Bassenthwaite Lake – are the last remaining native populations. “Originally it was present in four lakes in the UK, two in Scotland and two in Cumbria. The populations in Scotland are now locally extinct and that means the two populations in Cumbria are the last ones that are still native since the last ice age.”

“That freshwater from high up in a Borrowdale tarn might someday mingle with coral reef or form part of an ice cap or glacier…”

But that’s not to say Derwentwater is the ideal habitat for the fish. “Derwentwater is a relatively shallow lake, which is odd really,” Sam explains. “Vendace really like deep lakes with a very good, cold hypolimnion layer – the deep water layer. They have a very specific temperature threshold that they can survive in.” And they’re spawning habits put them at risk in Derwentwater, too. “They basically just lay their eggs on the sediment, they don’t build a nest like salmon and trout do. There’s a high risk of them dying through sedimentation. That’s when the eggs are covered with sediment and suffocate and are prevented from hatching into larvae.”

On past Bassenthwaite Lake, the River Derwent cuts the last of its course through the Cumbrian countryside and joins the Irish Sea. The Irish Sea goes on to join the Atlantic, the Atlantic the Pacific. That freshwater from high up in a Borrowdale tarn might someday mingle with coral reef or form part of an ice cap or glacier, habitats that face their own set of challenging environmental troubles. You’re not alone if you feel helpless in the face of these kinds of global catastrophes but at least part of the answer is simple enough: Start locally. Explore the landscape you live in and learn from the waters and waterways it needs to sustain it.

Do you need help creating and promoting content as part of your marketing? Get in touch with us here and find out how we can help.