An Interview with Photographer, Peter J. Walsh

We caught up with legendary photographer, Peter J. Walsh for a chat about his images of the early acid house scene in Northern England.

In our latest interview, we talked with Peter J. Walsh about his iconic photographs of the early days of club culture in the North West of England.

From raves in Rochdale to the hallowed halls of The Haçienda, Peter’s photos for magazines like City Life and the NME captured the atmosphere of the era with a distinct documentary style.

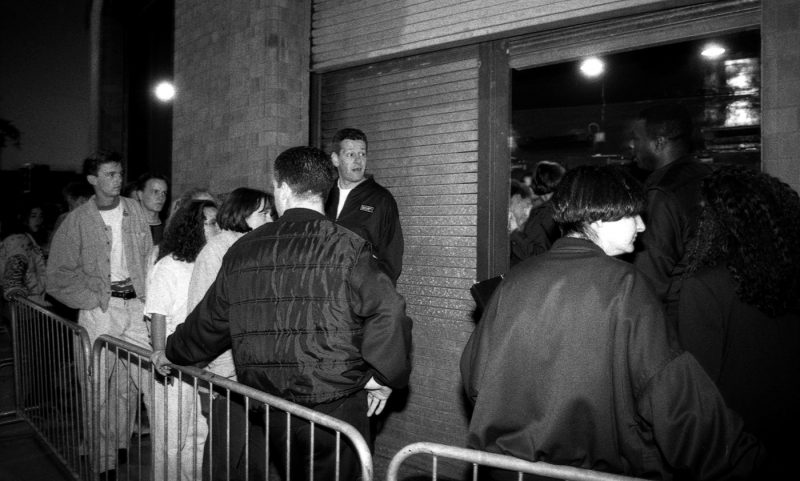

At a time when few would think to take a 35mm camera inside a club, Peter had the foresight to capture the whole picture—showing not just the sweat-soaked punters, but also the less discussed elements of ‘going out’… the bouncers checking bags… the lines of people queuing outside… the once-industrial buildings which housed the clubs themselves.

With some of his finest photos currently on display as part of the British Culture Archive’s People’s City exhibition at Manchester’s Refuge, now seemed like a good time for a chat about his work…

Starting back at the beginning, how did you get into photography? Was there a specific thing that set you off with it?

I’d been taking photos using the family camera—a Canon AE-1. My dad had a great eye for a photo and was a good photographer. He would help me take photos, showing me how to focus, use the light meter and helping me with composition.

My mum and dad then bought me my own camera, a Canon A1 and that’s when I really started to get into it. I became a member of Counter Image on Whitworth Street in Manchester to learn how to develop and print black and white photos.

I was interested in people and I started to photograph demonstrations in Manchester at the weekend. I used to meet two other photographers, Paul and John, regularly on the demos and we used to go to a cafe after the protest and have a cup of tea and a chat. They were going to start a photographers co-op, Profile Photos and asked me to join. I worked there for a few years shooting demos.

How did all this lead into you shooting the music stuff?

After I left Profile, I started shooting for City Life Magazine. I took my portfolio in to see one of the editors, Andy Spinoza—he liked my work and started giving me assignments and we’ve been mates since then.

They had different sections—features, sport, fashion, lifestyle, music and clubs. Each month I was assigned different jobs to shoot. I started taking shots of the local nightclubs and musicians.

Because of my documentary background I was used to reacting quickly to the situation around me and started getting some great nightlife and live shots. I then moved on to shoot features and fashion for the magazine.

Subscribe to our newsletter

I suppose shooting crowds at the demonstrations isn’t much different to shooting crowds in a club. You took a lot of photos of the clubs and raves around Manchester in the late 80s and early 90s — when did you first realise that something was going on there, something beyond just the usual ‘nightclub’ type fare?

I was sent to photograph Hot at The Haçienda. It was on a rainy Wednesday night, and as I walked in and started taking photos, I realised something was different. Paul Cons, The Haçienda’s promotions manager was trying to recreate the summer vibe of Ibiza inside the club.

The atmosphere was intense and euphoric, it was different to any other club I’d been in. It was like a wave that spread from The Haçienda around every area of the city.

Was it a conscious decision to document this stuff? I can’t imagine many people were photographing clubs back then.

Yes, I decided to document what was happening, because I could see that things were changing, and quickly. I thought that acid house would become as culturally important as the swinging sixties or the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. I wanted to capture this new movement.

I imagine that shooting at clubs like the Hacienda or the Boardwalk was fairly unpredictable in terms of what photos you were going to get. Were there certain things you were looking for when you were shooting clubs — certain expressions or miniature events?

I was inspired by photographers Robert Capa, Henri Cartier Bresson, Don McCullin, Lee Millar and Bert Hardy. I always remembered what Capa had said, “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” I’d look for interesting dancers, faces, or lighting. I would get right in on the dance floors and shoot three or four frames of ravers and then move to another spot and shoot again.

Because of my early work with Profile Photo Agency, I had been trained to shoot everything from many different angles and perspectives. Giving the photo editors at magazines a good selection of images to tell the story of the assignment you were shooting. So I would also get wides of The Haçienda or other venues to make sure I covered as much as I could for my own archive.

A few of the old 70s street photographers would have certain places they knew would work for photos—maybe a busy road crossing or a certain brick wall which a figure would always stand out well against. Did you have a similar thing in the venues you regularly shot? Would you know the best places to be throughout the night?

There were so many great places to shoot in The Haçienda—the main dance floor, the main stage, the Gay Traitor bar, the DJ Booth… I was spoilt for choice. I would wait for when the crowd were really up there and then start to shoot. I was shooting on film, so most nights I would only have a roll or a couple of rolls of film with me.

How did people react to you and your camera?

I was always in The Haçienda so a lot of people knew me, so I would get a positive reaction, but most of the time I wanted to document the moment so I would try not to interact with the ravers while I was taking the photos—only after I would give them a nod to say thanks. I also knew where to keep my camera out of sight in certain places in the club.

One thing I find interesting is that with your club photos is that you’d photograph the crowd, as opposed to more traditional ‘gig’ style photography which would focus on the bands. Was that an intentional thing? Was it a shift from ‘the icons’ to ‘the people’, or so to speak?

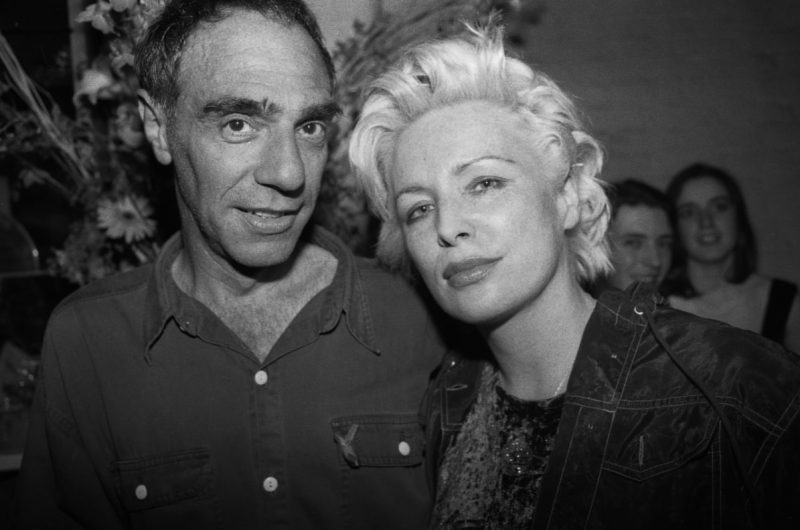

When house music arrived, I realised that I was at the start of an iconic cultural movement. I knew I had to document what was going on, as it would be important at a later date. It wasn’t just about the bands, it was about the ravers, the DJ’s, and the promoters as well, so for me it was about capturing as much as possible to archive this historic moment in time.

What sort of cameras were you using back then? Did you have a regular set-up you’d use?

Back then I was shooting using two Canon F1 cameras, all fully manual. It depended on the assignment I was shooting, one was loaded with colour, the other black and white film. If I was just shooting black and white, both would be loaded with black and white with different lenses on so as to be able to react quickly to what was happening around me.

I then purchased a Canon EOS 1 which had autofocus, which made it perfect for shooting in clubs. I also had a small Canon Zoom XL which I used to carry in my pocket so I could grab quick photos of Ravers and band members in the club if I wasn’t on assignment or didn’t have my main cameras with me.

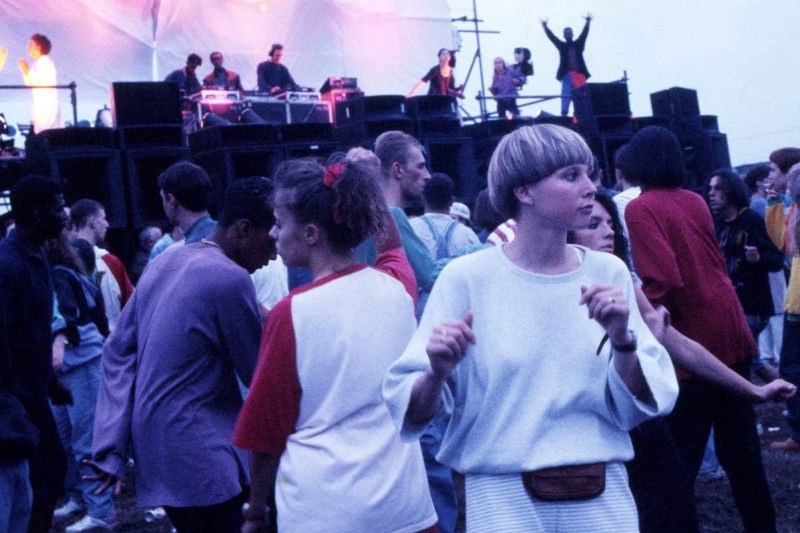

The Gio Goi lads Anthony and Chris Donnelly had put on the rave. It was wild. The locals and the police had no idea what was going on. I had been commissioned by the NME to cover the event. I knew I was going to get some great photos in the morning so I had to conserve film stock and stop shooting half way through the night. I got some great photos as dawn arrived the next day and people were still raving.

How did something like that differ from the clubs in town?

It was in the open air, a one off event, you felt connected to nature, raving under the night sky and watching the sun come up with everyone together. It was under the flight path for Manchester Airport and people were waving to the planes as they were coming into land.

At the same time as all this, you were shooting band portraits in a photo studio too. What was an average 24 hours for you like back then? You must have been pretty busy.

I was regularly working for the NME, The Face, i-D, Mixmag and the Japanese magazine Rockin’ On. It was full on for about four or five years. If I was shooting live gigs for The NME, the photos had to delivered round overnight. So it was back to the studio after the gig, process the negs, contact sheet the pics, choose the best shots and print them up. Then I had to package everything up and get to Piccadilly station for the first train to Euston at around 6am.

I would send the photos by Red Star, the British rail express courier service. I had Red Star packages, so I could walk onto the platform and give them to the guard on the train if I was running late. Then I would go home, get some sleep and be shooting a studio session in the afternoon.

Sometimes I would shoot three or four gigs night after night back to back. I was covering a lot of the north of the UK for the magazines, so I could be working in Newcastle, Leeds, Sheffield or Scotland.

What are you up to these days? Am I right in saying you work in TV?

I still work as a photographer and I direct documentaries and music promos. I also work as a cinematographer so work is varied and interesting. I spend time sorting out the archive. I’ve got thousands of negatives and transparencies that need scanning in.

I can imagine. Last question… was it hard to be ‘professional’ – working to tight deadlines for magazines, when a large amount of your time was spent up all night at clubs? It must have been a tough balance.

I had to be professional, my mates would be having a great time, but I had to stay focused and get good shots, I wanted to capture great images of what was happening. It’s a good feeling to see brilliant photos appear in the developing tray in the darkroom.

Peter’s photos are currently on display as part of The British Culture Archive’s People’s City exhibition at Refuge in Manchester throughout spring. See more of Peter’s photos here.