An Interview with Robert Jungmann, Manastash and Jungmaven founder

An in-depth chat with the hemp clothing pioneer

Hemp is pretty versatile stuff, used to make everything from homes to bio-fuel. Robert Jungmann has been crafting clothes out of it for just shy of thirty years, first with the outdoor clothing company Manastash, and more recently with Jungmaven—his line of hemp t-shirts, sweatshirts and bed-sheets.

In this interview, he talked us through the ups and downs of his time in the rag trade, from the early days, flogging wallets on a market stall, to becoming big in Japan, and beyond…

You started Manastash in 1993. What was the idea behind it? Not many people were making hemp clothes back then.

I moved to Washingston State from Phoenix, where we had just cacti. Living around trees and mountain landscapes– I loved it. But we’d go camping in a favorite spot and then go back to the same place the next year, and it’d be clear-cut. That would happen over and over again, for about five years.

Later when I was in college, the professor there told us about how rivers play such an important role in the Pacific North-West ecosystem.. He taught our class about watersheds and told us that if we grew industrial hemp we wouldn’t have to cut down all these old growth trees, which reduce erosion and keep the rivers healthy. That was my ‘aha!’ moment.

About the same time, my parents moved to southern California, by the beach. I had this large wallet, full of nothing I needed—all these photos, these cards I never used—and I thought, “What am I carrying all this for? I’m at the beach—I just need a little bit of cash.” So I made this little wallet out of backpack material. But then a hemp store opened up here in Seattle, called American Hemp Mercantile, and I put the two together to make a wallet out of hemp. And that’s when Manastash was born.

The more I learned about hemp, it was like, “Oh my gosh—here’s a plant that can really take some pressure off the trees.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Maybe a stupid question, but how does growing hemp save trees?

Well, anything you can make with a tree, you can pretty much make out of hemp. You can recycle paper, but you can’t recycle it over and over—it’s kind of like making a carbon copy of something—you only get so many uses out of it. But if you blend hemp fiber into the pulp, you can extend the life of the paper. My professor’s hemp lesson wasn’t directly about textiles, he was just introducing hemp as a fast-growing, sustainable alternative. All the things we use trees for, we can use hemp for instead–from building materials for houses to bioplastics.

That makes sense. Beyond the wallet, what else were you making at first?

I made rock-climbing chalk bags and Camelbak type hydration packs, then shorts and jackets. We’d put hang-tags on them, which were almost like small books, detailing all the things you could do with hemp.. Nobody knew about hemp back in 1994, it was all new information. The Emperor Wears No Clothes by Jack Herer was pretty much all the information that was out there, so we’d share information out of that book.

Almost like street preachers handing out pamphlets?

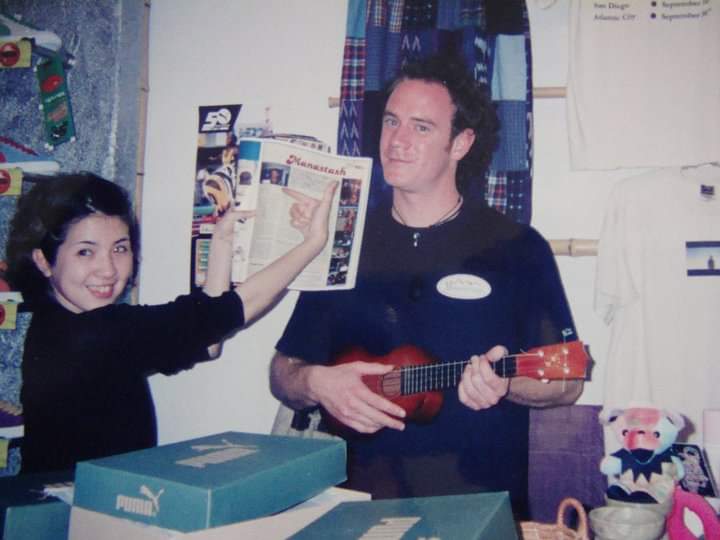

Yep. It was all about education. In the Manastash days we’d go to the Fremont Street Festival, which was every Sunday. We had a little booth, and it was like that—we were on a soapbox preaching hemp. And it was like that for the first five years—or actually longer than that, because in 2000 it felt like things kind of went backwards.

Why was that?

Here in the U.S., there were the Bush years, and then we had 9/11. A lot of things took a backseat—nobody was interested in hemp. Hemp really needed an image boost, because these hemp stores which had opened up all across the country were also selling bongs and things like that, which wrongly associated hemp with the drug culture. Many of the hemp shops were short-lived and didn’t do enough to push industrial hemp into the mainstream.

How were you making things back in the early Manastash days?

In the very beginning, I was making things in the attic with my best friend’s mom. I’m a horrible sewer, so I did all the design, and she did all the sewing. And then I did the dye-work in the washing machine in our basement. I had dated a girl in high school who’s mom was making Roffe jackets. Do you remember Roffe jackets?

No, what were they?

They were ski coats. So I reached out to her, and she knew someone who could help me out. And that’s how I got introduced to the Seattle fashion machine. In the 90s, there were still a few clothing factories and dye-houses in Seattle.

There was a place called Seattle Wash which did cut-and-sew and garment dying. That helped us in the very beginning because we couldn’t hit any minimums, so we’d have to make 500 units of something, but then we could dye it up in a bunch of different colors.

“Anything you can make with a tree, you can pretty much make out of hemp.”

This is why, even back in the early days, our stuff looked broken-in and had an assortment of colors. Out of 500 units, we’d maybe split that over ten colors. There was a place that specialized in tie-dye too, so we’d think, “Let’s tie-dye those shorts.” Back then you only saw tie-dye t-shirts, but we’d tie-dye everything. It was kind of fun.

It seemed like there was a lot of stuff going on around Seattle back then. KAVU was started out of there around a similar time too. Where did this burst of stuff come from?

That’s a good question. These things come in waves. For the Pacific NorthWest back in the early 90s, everything was happening here. As a DJ, I remember getting the Pearl Jam Mookie Blaylock tape. Just the week before I’d been listening to Nirvana and Soundgarden, so I was like, “What, this is from Seattle too? This is insane.” I’d joke with Barry at KAVU, saying, “You’re like Soundgarden and we’re like like The Screaming Trees.” I don’t know what was going on, but there was something happening. Maybe it was because there were more resources at our fingertips, and people were looking for something new..

With Manastash I’d think, “I love how these vintage pants fit, and I love how Carhartts are so rugged, so let’s combine the two.” And there were factories who were willing to take the time to do this stuff. It was a great time to be in Seattle. I remember it felt abundant, but at the same time we were living on twenty bucks a day, if that.

How did people react to it?

They thought we were selling weed. I remember going to the Outdoor Retailer Show in Reno, and we had people stopping by the booth going, “What the heck are you doing? Are you selling weed clothes here?” We actually had the Outdoor Retailer people come by and check us out. We tried to explain that this clothing is good for the environment. We talked them into letting us stay, but it was dodgy. We did end up getting quite a few orders though.

I remember the next summer we went on a hemp tour. We took two Volkswagen buses, and I had an Astro van, and we were on the road, travelling, doing every mountain bike race that we could. We’d race in them, and we’d get a booth—this bamboo hut with palm fronds—selling our hempware. The NORBA mountain bike race people loved it, and told us about a rock climbing event. So we’d do that. And then there’d be a balloon race, and we’d do that. We did everything we could for a month of a half.

I remember sending flowers to the Outdoor Retailer Show, saying, “please, let us in,” and they did. I remember that year the Patagonia crew were outside the booth thinking, “Hmm, there’s something to this.” They’d already been thinking about it, but we were there, doing it. A couple of Japanese distributors were interested too, and about six months later, on Christmas Eve we were having a party, and over the fax machine this order from Japan came through. It was a $20,000 order, it was insane. We were so excited. It was our big break.

Why do you think it took off in Japan so much? That seems like a regular occurrence for interesting brands. What’s different there?

It seemed like Japan was really open to new things happening in the US. That was my take on it. I don’t think it was because of the environmental thing, at the beginning, but our distributors went with that, and it had legs. Patagonia was already big in Japan, and I remember t-shirts over there where people had combined the two brands, ‘Patastash,’ or ‘Managonia.’ That was cool. I think the kicker was that we were trying to make a difference—it had core value and it was true. We weren’t saying, “Hey, we’re going to give money to something to make ourselves green, even though we make something really crummy for the earth.”

Yeah—there was something authentic there. The brand was eventually sold to a Japanese company. What happened there?

Yes—it’s a little bit of a sad story. I’ll make it brief. We had an investor come in, and he sold us on this idea that we should make everything in China, and I bought it. It worked out well for about a year, and then in the third season the product was complete garbage. Japan cancelled their entire order, and it put us into a spiral.

The investor said, “I’ll take over the debt, I’ve got this,” and he just asked for my voting rights—because I owned 80% of the company at the time. So I sold it to him, and then he fired me, took over the country and sold it. I got squeezed out, and had no control. It was like getting your baby ripped from your arms—it was something I’d worked on for nearly ten years. Lesson learned, never sell your voting rights.

That story seems quite common with companies that are growing. They seem to reach this point and then these shady characters come out of the woodwork.

I’ve had a lot of friends go down the same path. It’s unfortunate—it does happen a lot. You get to this point and you’re like, “I need investors.” No you don’t—you need to slow your role and get better at what you’re doing, and grow at a healthy pace.

What did you do next then?

So I moved to Costa Rica and chilled out for a while. And then I started Jungmaven—trying to start over and not make the same mistakes. It was hard to let it go—it took me years.

What was the idea with Jungmaven?

I moved to Costa Rica in 2001 and the hemp jersey t-shirts that I took with me lasted a long time. Everything else I had fell apart in the jungle. And that’s one of the reasons I started Jungmaven—here’s a product that everybody needs.

With Manastash I made everything from golf bags to skateboards, but the t-shirt was more universal. Why not just make a really good t-shirt? That’d be the easiest way to introduce everybody to a quality hemp product. That was one of the missing links too—some of the hemp products were just not made well back then. So we just did a basic t-shirt and a long-sleeve—black and white—it was real simple.

Had attitudes changed to hemp by then?

That was in 2005. It was an interesting time—there was a lot of competition out there doing different things—Livity and Satori were the hot brands for hemp, and iPath shoes—but there was really nothing in the outdoor retailer world. Then in 2008 the economy just cratered.

It took a couple of years, but all of a sudden ‘Made in the USA’ was interesting again. There were a handful of small stores, like Hickory’s, who were really focussed on that—and so we brought Jungmaven to that market.

And then Fjallraven picked it up in 2011, and that really helped us out. Fjallraven was a new concept for the US, and we had a giant table in their store, with all these different colours of t-shirts. That really helped us get into a whole new market. And that’s how we emerged in this fashion / outdoor world.

“Before it was just about consumption, but by 2011 people were thinking, ‘What brings me joy? What has value?'”

There was a definite push for authentic, well-made clothing at that time.

All of a sudden, less was more. Before it was just about consumption, but by 2011 people were thinking, “What brings me joy? What has value?” That ethos has only continued to grow.

We were definitely struggling at points though. We started making black and white t-shirts in 2005, then we started making pants and jackets in 2007, but then in 2009 we went back to those black and white t-shirts.

It sounds like a wild ride in the clothing industry. There’s just endless highs and lows.

I think it’s super fun. That’s what I enjoy the most with it—trying to see what trends are coming. I always compare it to music, and we’re putting out a new album every six months. We’re not reinventing the wheel there, but we’re just trying to push the needle a little bit in the right direction.

I should add that back in 2009, when I was struggling, I thought, “I wonder what Manastash looks like now?” So I found them online, and it looked amazing. So I called them up and told them that I loved what they were doing, and then they called me back asking if I wanted to help grow the US market. And that’s actually how Hickory’s and Fjallraven found Jungmaven—because they came over to my booth looking for Manastash. So Manastash actually helped me out at one of my darkest hours—it came back as a teenager to save me.

That must have been nice. Do you think as someone who’s been working with hemp for a few decades now, you’ve helped inspire other brands to do the same?

Yeah, and I continue to encourage it. We’re trying to make something that people want to emulate. If someone else uses hemp, then that’s one more product on the market that’s made with an environmentally friendly textile. We did hemp sheets and bedding about four years ago, and now there are so many people doing hemp bedding. And why not? It’s a great thing to sleep in.

Did what happened with Manastash affect how you do things with Jungmaven?

A big lesson I learned, and one that should be told to people who are starting a new company, is that growing smart and staying true to what you believe in, is so important. It really dilutes the integrity of the company once you bring in people who are just in it for the profit.

Brands can quickly lose their flavour when they grow too fast.

Yeah, if all of a sudden we start making sunglasses and shoes and hats—just putting our label on something—then we’d lose a bit of who we are. I like it when people say, “You do this really well.” or, “This person does that really well.” The product quality is diluted when a brand tries to be everything to everyone.

Definitely. Slight change of subject, but what do you do outside of all this? How do you shut off from running a clothing company?

My girlfriend has a five and an eight year old, so they’re keeping me busy. We go camping and I try to go mountain biking as much as possible. And then there’s yoga and meditation—and I always put time in on a treadmill. I’m still getting under a seven minute mile pacing on a four mile run, and at 52 I feel good if I can keep at that level.

You’re doing alright then. Is it important to have a balance? People often get burned out if they run their own business.

Yeah absolutely. I met with the gentleman who brought Ikea to the U.S. one day, and had a great talk with him.One of the things he said that has stuck with me was that, “If you go into the office, try to be 100%—and if you can’t, then think about maybe not going in.” If you’re not healthy, then you can’t do a good job for your team.

For me, being healthy means playing outside, jumping in the water somewhere or going mountain biking. Just being active and getting my heart rate up everyday. It keeps you alive, and it keeps everything you’re doing feeling alive too. If you put too much time into your work, it takes over your life.

Yeah, I suppose what’s the point in doing all the work if that’s all you’re doing? Thanks a lot for taking the time to talk to us. You’ve already given us a few words of wisdom here, but do you have anymore wise words to end this with?

I’d say if there’s one good piece of advice, it’s to look at consumption. Think, “Do I need this? Is it valuable?” We’re voting with our purchases, so everything you invest in, you are adding power to and advocating for. So take the time to research what you buy to make sure you’re supporting a product that aligns with your values– and hopefully can make this world a better place in some way.