An Interview with Like the Wind Magazine’s Simon Freeman

We talk with the independent running magazine’s co-founder

Since 2014, Like the Wind magazine has been asking the question ’why do we run?’

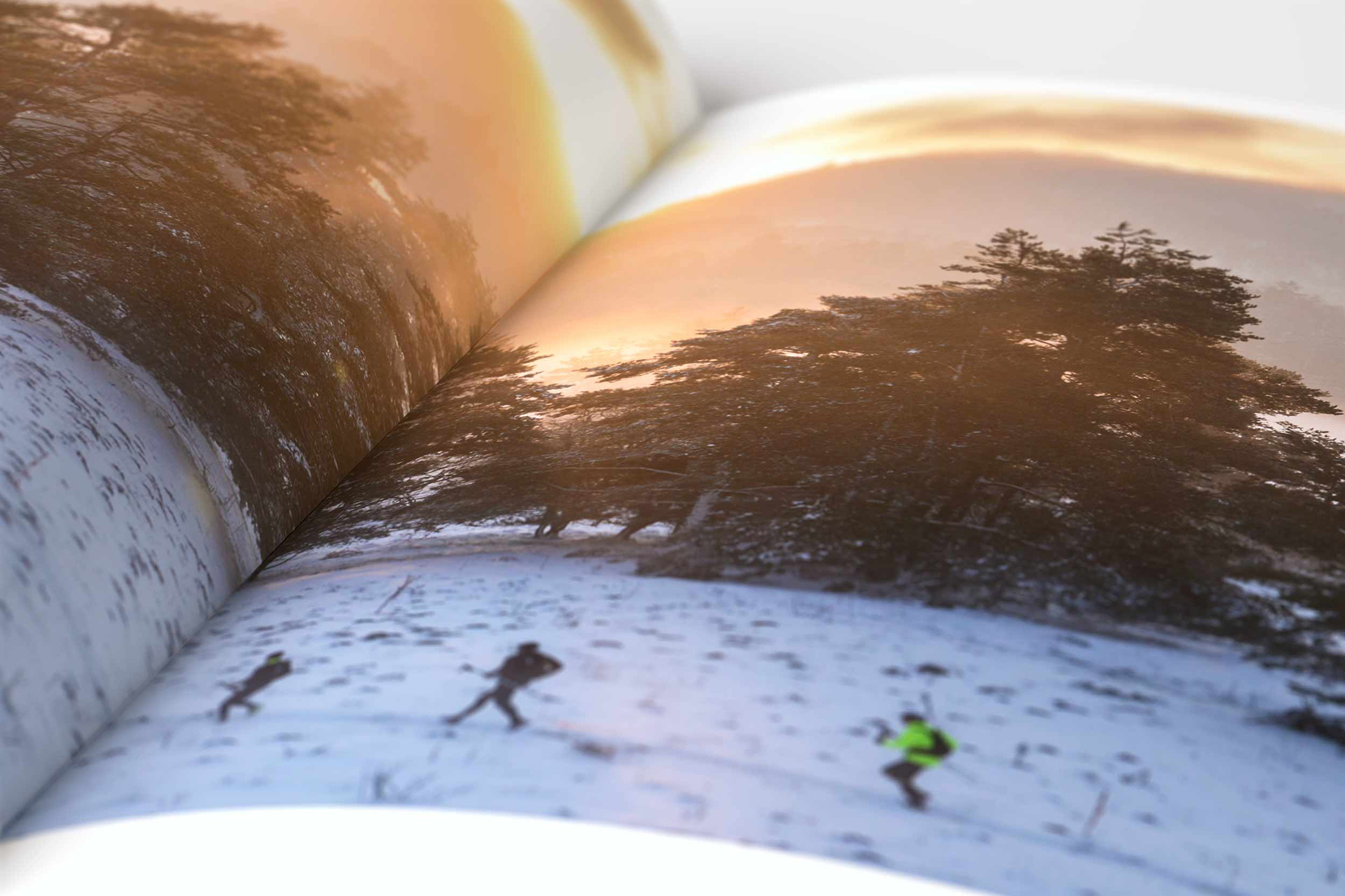

A world away from your typical running magazine (and those endless pages of product reviews), each issue of Like the Wind is filled with personal tales of running in the real world, getting to the bottom of what drives people to hit the pavement, track or trail.

With the 25th issue about to be released, we talked with co-founder and editor Simon Freeman about running, magazines and… er… running a magazine.

Starting from the beginning, how did you get into running? Was it something you were always into?

No! I basically did sport somewhat under duress. I went to university, and in my first term of the first year, I broke my leg playing rugby. And I felt like it gave me the excuse I was looking for to not have to do anymore sport. I then focussed on drinking beer, smoking cigarettes and having fun, and that continued right the way through until I was nearly 30.

But then on Christmas Eve when I was 29, I’d been out the night before I’d drunk far too much and smoked far too much, and I was in the bathroom with a massive hangover, cleaning my teeth, and I just thought, “What am I doing? This is madness.” I wasn’t even 30, and I couldn’t run up the stairs without getting out of breath. I was so unfit. I thought, “Right, I’ve got to do something.” So I quit smoking there and then and I massively cut back on my drinking.

Because I was trying to lose a bit of weight, a friend of mine who had done marathons said I should try a bit of running. And I went for a run—I ran around the block, which I now know is just over a mile, and it took my about 12 minutes. I felt sick at the end, but I also felt elated, so a couple of days later, I went again. And I just kept going, and it became the thing that I looked forward to—I really got bitten by the running bug. My friends would start saying about their running club, so I’d go down, and there I’d hear about a 10k race, so I did that. It was all incremental. And then, I got obsessed with marathons.

What was your first one?

My first marathon was the Halstead Marathon. I’d been running for two years by that point. And I ran it in 3:37. I felt absolutely dreadful when I finished, and couldn’t believe the pain in my legs, but by the time I’d walked from the finish line to the car park, I knew that I’d be doing another one.

Why do you think that is? What makes people want to put themselves through absolute pain again and again?

One of the things I love about running is that there’s an element of input and output. You can get better just by being a bit cleverer with your training. And the thing about running marathons, to a degree, is that it’s totally comparable. If I say to you that I ran 3:37, and you’d run 3:35, then you’re two minutes faster than me. There’s no points for style, there’s no objectivity.

It’s straight up.

Yeah, it’s like a lot of endurance sports, it’s quite objective. And then if you get into the biochemical side of things, the pain in my legs was fleeting, but the endorphin rush and feeling of accomplishment was really addictive.

There’s a lot of history around the marathon as a distance, and it is a kind of perfect distance—it’s just a bit too far to be able to blag it. You and I could meet up and run 10k today—it might not be pretty, but we could do it. But beyond 20 miles, you’ve got to train for it, and be mentally prepared, and that’s part of the addiction.

Subscribe to our newsletter

The fact that everyone there has invested something into it must add to the atmosphere too. I’ve never ran a marathon, but I imagine there must be a pretty big element of camaraderie.

100 percent. And whether you’re at the front of the pack running two hours and change, or you’re taking six hours, it’s a huge effort. I love the camaraderie of standing on the start line—looking around and thinking how everyone has put in maybe 10 or 20 weeks of really focussed effort, and probably years of development to get to that point. It took my seven years to get to my best marathon time—and that was seven years of trying to get progressively quicker.

That’s a lot of work. How many have you done?

30 odd. I really got into it. I was doing several a year. I was always trying to run quicker, and I think part of the game is that you’re always trying to push yourself to the limit. If you want to run a particular time, you’ve got to start at the pace that will allow you to finish in the time you want. My personal best was 2:37, which is a six minute mile. I couldn’t run the first mile in ten minutes, and then speed up, as I’d never catch up. And it gets to the point where if one of those minutes is six and a half, you can’t even get that time back. You’re literally right up against your limit—whatever that limit is.

“I’m always fascinated in why people do these things—what motivates them—and that’s why we started the magazine.”

You might be more experienced, but you’re giving yourself a different challenge. The following year I ran the same marathon in just under three hours, and if I’m honest, I was actually quite bored.

People like to make things hard for themselves.

I can’t remember who it was, but a cyclist said, “It never gets easier, you just get faster.”

Maybe it’s human nature to want more.

Right, can you go faster? Or higher? Or further? For a lot of people it’s a personal challenge. It’s curiosity. Wondering how fast I could go.

How did this lead into doing your magazine then?

A year after I’d run my marathon PB, my wife and I were in Chamonix, running around the Mont Blanc mountain range, stopping at mountain huts on the way, and that’s where we had the conversation about the magazine.

I’m always fascinated in why people do these things—what motivates them—and that’s why we started the magazine. The strap-line for Like the Wind is, “It’s Not How To Run, It’s Why We Run. I think the ‘how’ is relatively simple to answer, but the ‘why’ is what fascinates me, because everyone’s ‘why’ is different.

And it suddenly opens up all these stories. It’s bigger than just running.

Massively. And we’ve had the privilege of having some unbelievable stories of people opening up about things in their lives—these beautiful, traumatic, incredible things, that running helps them make sense of. It could simply be like my story—realising I’d made some fairly big mistakes in my life that I needed to correct, or people dealing with serious trauma, or maybe doing stuff for charity and other people. The ‘whys’ are really powerful.

And I’ve yet to find somebody who can’t, in some way, illuminate on the ‘why’. Even if they just go and do a park run every Saturday, there’s always something behind that.

There’s still something driving them. And that’s far more interesting than reading about heel strike.

I couldn’t possibly comment. When we first started the magazine, I didn’t read running magazines anymore. I didn’t need to be told what the best trainers were for my running gait. Maybe that was arrogance—but I felt like I’d been doing it long enough that that wasn’t sufficiently engaging for me.

But my bookshelf is full of biographies by people writing about what drove them to do what they did, and we just thought, maybe something like that, in magazine format, would be something that people would be interested in. And thankfully, the last six years have proven that it was.

After the idea—how did you then turn it into a magazine? What was the process?

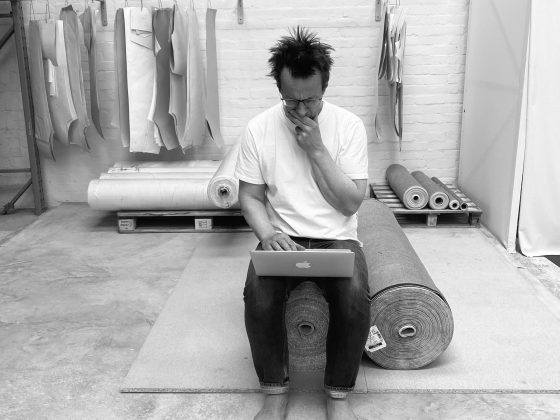

We thought, “We can’t be the only people thinking this now.” So there was a sense of urgency. If we didn’t act on it, and someone else did, we’d have felt stupid. So I started e-mailing people in the running industry, authors who’d written books and elite retired athletes who I’d read about—I was literally sending them an e-mail, saying, “Hey, I’m launching this magazine, can you tell me a story.” And we started getting the content in. Julie, in the meantime, downloaded the free trial of InDesign, which gave her 30 days, and taught herself how to layout the pages of a magazine. And it was a simple as that.

I look back at the first issue now, and it’s amateur hour. But, it was done, and that allowed us to say that we were the only independent running journal in the world. And we started gathering momentum by word of mouth.

At that time there was a big movement towards these more thoughtful, less news-based magazines, with things like Rouleur…

Yeah, Rouleur was a massive inspiration, and there was another magazine, which has sadly now stopped, called The Ride Journal. I think a lot of it came from cycling. There was a book called The Rider by a Dutch chess grandmaster Tim Krabbé which is a short fictional account of a cyclist in a race, and that book got translated into English—and somebody said to me that they thought the translation of that book sort of kicked off that interesting storytelling in cycling.

The other thing, which shouldn’t be underestimated, was that there was quite a shift in the physical production of magazines. I used to work at a printers as an account manager, and back then you couldn’t go to them and say you wanted a 1000 copies of something—the cost would have been astronomical. But there were changes in technology which meant that set-up costs for printing dropped. Suddenly you didn’t have to start at 10,000 copies.

Maybe people realised that the internet wasn’t everything too. It does the job for the news and reviews, but to me, a long article with nice photographs will always look better in a well laid-out magazine.

I think so. If you want a marathon training plan, go online—there’s thousands of them. But I don’t think people sit there with their phone in the same way they would with a magazine. Somebody once said to me that the best thing about Like the Wind was that you needed a bookmark to read it. You sit down, crack open a beer and spend maybe 15 minutes reading a piece—I just think that’s a wonderful way to engage with a piece of content… not just scrolling. The internet and social media is all wonderful, but I’d argue that resurgence in independent publishing is driving by the fact people want that moment away from the screen.

And you are on the internet too. It’s not ‘digital vs print’. You use each tool for what they’re good for.

Right. And the mission of Like the Wind is to inspire people, so I’m really happy that we publish content online or publish social media posts, as it’s achieving the same goal, in different ways. I really want to get into other ways of telling these stories, whether that’s with films or podcasts or books. If you go out for a run, you can’t read a magazine, but what you can do is listen to a podcast. Or maybe even the depth we go into with the magazine isn’t enough, and what people want is a book, with 300 pages on something. So that’s another interesting channel we want to develop.

You cover a lot of events on the fairly extreme side of the running world. Things like the Barkley Marathons or the Zegama. Why do you think it’s important to talk about these events?

We try really hard to cover the whole gamut of running. We have stories of people who go out two or three times a week for a 45 minute run because it’s a way for them to heal their mental health—and that has as much value for me as someone trying to do the Barkley’s Marathons—so we do make sure that in every edition there is the full gamut.

But it’s got to be said that if you’re trying to do something as insane as the Barkley Marathons or racing Zegama, the ‘why’ behind that becomes even more pointed. People aren’t training to do that kind of mad stuff because they’re bored. To push the outer limits of human ability, there’s something else going on there. It might be something as mundane as curiosity, but it’s not the kind of curiosity that convinces you to try a different flavour of ice-cream.

And I do think there are limits to human ability. I don’t know where they are, but if you’re running two hours for a marathon, I don’t think anyone will run one in one hour.

There’s got to be a limit somewhere. There might be new super-foods out there in the future, or maybe ways to train, but there’s got to be a point where it maxes out.

We’re still seeing incremental improvements in certain areas—and people are still going to run faster, but for example with the 100 metres, Usain Bolt’s record may be broken, but it won’t be broken by someone running eight seconds. That seems inconceivable.

And if it kept going like that, someone would eventually be running it in two seconds.

And that’s not possible.

Although maybe in 100 years people will think otherwise.

And isn’t that fascinating? So I do think these stories of people on the outer limits of physical human capability are important. With the Barkley Marathons, the whole point of the race is to allow people to get to the absolute limit of what they’re capable of. That’s what the guy who set it up is trying to do. And in order to do that, pretty much everyone has to fail.

So with my editor’s hat on, if I’m trying to get at what drives you as a runner, those people and their stories are particularly tantalising. What they’re trying to do is crazy.

Have you noticed a character trait that links the people at that level?

No, and that’s really interesting. Although I think at the very extreme end people often have that growth mindset—they’re the sorts of people that look at a challenge, and wonder whether it’s possible. And that’s not limited to running—you get the same thing with climbing mountains or even business.

What other races are there at that sort of level?

There’s hundreds. There are races in the UK like the Spine Race, or the Dragon’s Back. And then UTMB—that’s a huge challenge for everybody involved, whether you’re winning it in 20 hours or struggling around and finishing it just inside the cut-off, which I think is 50 hour—it’s an enormous challenge just to stay awake. And then there’s the Bob Graham Round. Far more people fail than succeed—and only a tiny percentage of the population even try.

In the US there’s a race in Death Valley called the Badwater, where you’re running in the hottest and driest place in continental USA. People are running along this road, and their shoes are melting because it’s so hot.

You can count me out of that one. Is the rise of this kind of extreme race a reaction against life, generally, becoming more comfortable for a lot of people?

Absolutely. For a lot of people it’s a physical challenge, something they can throw themselves into and feel proud of. I think a lot of people who get into running have realised that a sedentary lifestyle isn’t great.

And often the difficult, challenging parts of life are the ones people remember. Obviously people don’t want to remember stuff that’s too negative… but you’re more likely to remember some sort of holiday hassle than the day you sat on a computer.

I just read a book called The Other Side of Happiness by a guy called Brock Bastien, and he talks about the fact that comfort and happiness aren’t the same thing. There are plenty of very comfortable people—millionaires in beautiful air conditioned apartments or lounging on boats, but it doesn’t make them happy. Whereas, you know what it’s like—the first cold beer at the end of a really long, hot run, is the greatest thing on earth. You feel like you’ve earned it.

“You want enough challenge in your life to feel so you can feel like you’ve pushed yourself and achieved something—and for a lot of people, running represents that.”

If you just had cold beers every afternoon, they’d lose their appeal. There’s something in our psyche that means that we crave the reward more than we crave what the reward is. I finished a race in the Alps where I was running for 18 hours, and on the finish line they were giving away this dreadful beer, but I remember thinking it was amazing. I’d worked it and I’d earned.

You’ve got to struggle a bit.

There’s an interesting idea that not enough struggle isn’t good, and then too much struggle isn’t good. There’s a middle ground. People don’t want to be living in abject poverty or living in pain, but you want enough challenge in your life to feel so you can feel like you’ve pushed yourself and achieved something. And for a lot of people, running represents that.

Going back to the magazine. I’ve noticed you feature a lot of illustration—was that important from the outset. It certainly sets your magazine apart.

Yeah, we definitely wanted it to look unlike any other running magazine. And we wanted it to be something that people would value, and the design played a bit part in that. We buy the best paper we can, we perfect bind it—we try to create a sense of longevity. And a picture tells a thousand words, so good photography and good illustration enhances the stories.

When we work with illustrators, the stories are available to them, but we don’t give them a brief. They give us their visual interpretation of it, and we’re often really surprised. And that’s really cool as well—it adds another dimension to the words.

You might take one thing from the story, whereas the illustrator might be inspired by something completely different. How has the magazine changed over the years?

Very early on, a friend of mine, who was a sub-editor who had got into running, contacted us and volunteered to help. And then on issue 10 another friend of ours who is a graphic designer got involved. Up to that point it’d all been Julie. So there’s four of us now, and when he joined there was a bit of a step change and the design of the magazine took a leap forward. There was another step-change in issue 24 as we worked really hard on the design and the lay-out.

The whole Covid-19 situation made us realise that the magazine was important. I think we’ve realised the value in what we’ve got, so we’ve responded to that by trying to up our game. And then, as I was saying earlier, whether it’s through books or podcasts or films, there are lots of opportunities for us to do more.

I suppose that’s sort of the same as what you were saying about running… about how you always make it a challenge. It’s that same drive.

Yeah, how can we take this a step further? There’s a quote that appeared in the magazine by Maya Angelou, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” And I think we’ve got such amazing access to these stories that we sort of owe it them to have more ways of telling them.

What other magazines do you look at?

Rouleur remains one of my favourites. Sidetracked—I think what John does is phenomenal. The Surfer’s Journal—I’m a terrible surfer, but I absolutely love it, and I think this magazine is stunning. I really like Another Escape, I love Huck, as I think they do lots of good things around campaigning and raising awareness of issues. I have to stop myself from buying magazines.

That ‘edition’ mentality comes into it with magazines. They’re numbered—so you want them all. I suppose we’ve maybe talked for a while now, so wrapping this up, have you got any wise words to end this with?

It’s probably a bit cheesy, but if you’re curious about running, or independent publishing or anything else, the key thing is just to get started. I’m embarrassed about my first run, and I’m embarrassed about the first edition of Like the Wind magazine, but do you know what? They happened, they’re out there, and they were the first step. I’m really passionate about people that have an idea that they think is going to bring benefit to other people, and just getting on with it. It might not be beautiful at first, but it’ll be done. Just get on with it.

Without issue one, you wouldn’t have issue 25.

Absolutely. When we first started, we had quite a few people who messaged us saying, “I had the idea of publishing an independent running magazine ten years ago,”—but they didn’t do it. Done is beautiful. Just get on and do it.