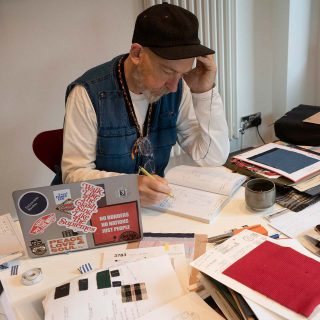

An Interview with Jelle Mul—Patagonia Europe’s Senior Marketing Manager

Behind the scenes at Patagonia

Patagonia’s boundary-pushing approach to the outdoor clothing industry is well documented. From their forward-thinking use of fabrics like fleece to their almost ‘anti-marketing’ marketing—such as their famous ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ Black Friday advert—they’ve long taken the trail less-traveled—garnering serious respect in the process.

But what does that mean for someone who works there? Jelle Mul is Senior Marketing Manager for the EMEA region—helping to share the stories that matter to the brand with audiences across Europe. Keen to find out what goes on ‘behind the magic’, we called him up to talk about work, community and the importance of staying positive.

You’re the senior marketing manager at Patagonia for Europe, the Middle East and Africa—what does that entail exactly?

I’m responsible for brand marketing at Patagonia—so being the senior marketing manager means I’m running the brand side of things, managing a team of people who all have functional expertise, whether that’s in PR or social media, or maybe they’re heading up our ambassador programme—looking at our events and our content—it’s all those different elements.

Globally, we are a Ventura, California-based company so I collaborate a lot with our US team on campaigns, but then also there are a lot of campaigns and stories we originate from Europe. That goes from Blue Heart and Vjosa Forever, a series of long-running campaigns to save free flowing rivers in the Balkans, to Vanishing Lines, a film around ski-lift expansion in the Alps, and Run to the Source, an exploration of Black British History that’s intertwined with this incredible FKT challenge, our ambassador Martin Johnson running the length of the Thames River, for instance. And then there are product campaigns on things like Yulex wetsuits, made from FSC Certified natural rubber instead of petroleum-based neoprene, through to our long-standing Fair Trade programme or technical product conversations… so I try and bring all these stories to life.

Quite a range of stuff then. Is it one of those jobs where everyday is different?

We say a lot that there’s never a dull moment—and there isn’t. All of a sudden something important happens… For instance, we have a campaign at the moment around community energy that we launched last March through our We the Power film. Now, with issues such as the impact of the war in Ukraine and increasing energy poverty across Europe, the energy transition is more important than ever—so we’ve re-looked at that to work out how we can best support the movement through ever-shifting events. It constantly changes.

Quite often with clothes you’re working a year in advance—whereas with these projects I imagine you’ve got to be more reactive and operating in ‘the now’.

100 percent! We run a seasonal calendar where we plan out the stories we will communicate—whether they’re product or environment focused—and we do our best to get everything in there, but then all of a sudden this little forest in Holland might be under threat due to a car manufacturing plant expansion, so we pivot to how we can help with that in the extreme short term.

You’ll have this set calendar, but all of a sudden you’ll come to the office in the morning and it’s like, “Well, we need to support this right now—how do we do that?”

How do you deal with working like that?

You hate it, and you love it. When you’re working on those campaigns, once you’ve figured them out, they’re really good. When that machine gets running, it’s really fun. It can be frustrating sometimes, because it’s last minute stuff—but it’s fun.

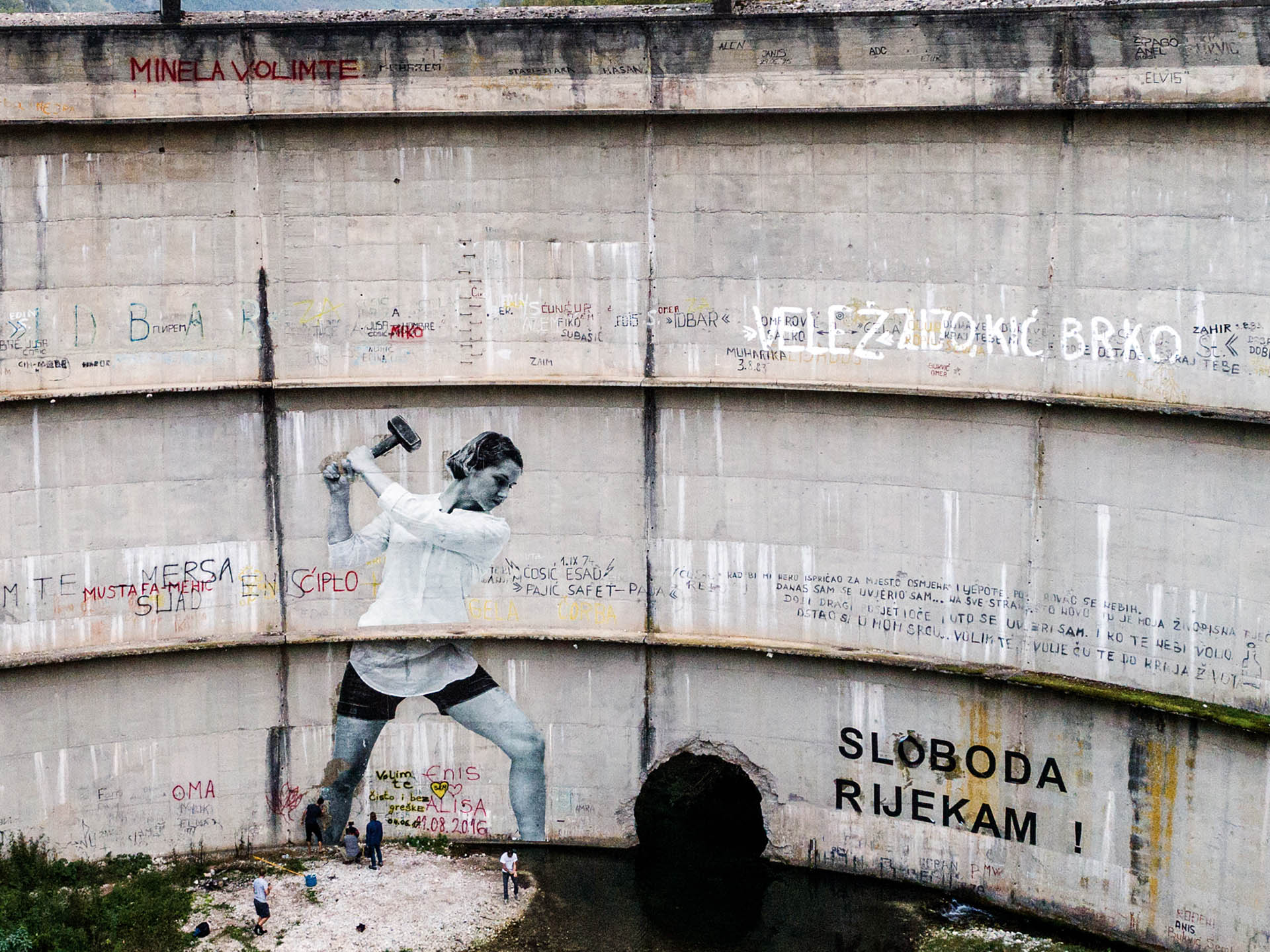

We’re running this ongoing campaign to fight the building of over 3,400 proposed dams in the Balkans. And as part of our film shoot, we met a community of mostly women who were standing together in protest on the access bridge that would bring heavy machinery to dam their river. Their drinking water came from that river – it was the life-blood of their town. They stood there together, day and night for over a year and, with relentless campaigning, they won. The dam was never built! That’s worth every sleepless night or every extra hour you work—and that’s what’s cool—you can work on something that actually matters.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Patagonia is often held up as the role model of how to run a clothing company well—how does it differ from other companies?

I can’t really speak on behalf of other companies, but what feels unique at Patagonia is that there’s an owner who cares about one thing—saving our home planet—and that trickles down to everything and everyone who works for the organisation. So for instance, we don’t have a CSR department—which most companies have. Instead, every single person – from IT and HR to Finance, everyone – is responsible for implementing our purpose in their daily work.

There’s not just one person with a clip-board waving their finger.

Yeah—or there’s not just one person trying to get the product department to use recycled materials—it’s here in all elements of the organisation, and I think that makes a really big difference. I think the main reason people appreciate Patagonia so much is that it’s not just the ‘marketing sauce’. My role as a senior marketing manager is to tell the stories of the things we do, or have done—whereas often with companies their marketing is the beautiful sauce over something that isn’t really there.

Do you think the fact Yvon Chouinard is heavily involved makes a difference? A lot of outdoor companies are sold off when they reach a certain size.

Yeah—the reason we’re 100 percent about people-over-profit is down to ownership. You see a lot with bigger, publicly-traded companies that they have shareholders who want a certain growth number—and that’s completely different for us. That doesn’t mean those companies can’t do things like Patagonia, and we’re seeing more and more that they can.

It’s not like you’re fighting against a board of directors.

I’d argue that it’s often the opposite. The owners go further than us—and we get challenged a lot on whether we’re doing enough. I think the starting point of the brand was just the right starting point—our old mission statement was to build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm and use the business to inspire and implement solutions for the environmental crisis—and they’re still our values. “Cause no unnecessary harm” is a really good starting point for running a business—a lot of businesses are extractive, including our own—they take resources to build the things they want to sell, but the thinking from Patagonia is how can we mitigate this—let’s hold ourselves accountable.

“I think the company really proves that’s possible if you start with a different sort of thinking.”

At Patagonia you won’t hear anyone say “we’re sustainable” because we’re a responsible company—we try to be responsible, but building a product does have an impact on the environment.

All of these different elements add up to the company we are—and that’s the starting point of the conversation. Yes, we need to be a profitable company, but not in spite of everything—these elements are extremely important for the organisation, and that’s where the challenge often lies.

I think the company really proves that’s possible if you start with a different sort of thinking. Internally here, a lot of people have conversations with other companies—as we want to help other companies too. They’re all on their journey, and they might not be perfect, but it’s step by step.

The customer is a lot more informed now. They don’t just want a fleece—they want a fleece with a story.

Yeah, I think the success of Patagonia probably proves that. The consumer is more and more conscious of what they buy, and why they buy it. We have a programme called ‘Worn Wear’ where we repair peoples’ gear—it’s an educational tool, showing people that they can repair products. And then we’ve got our Ironclad Guarantee, where we fix Patagonia products until they’re no longer fixable. And we just see more and more traction with these ideas—and we see people are eager to do this stuff. As much as there is fast fashion, there is another way.

The company was founded in 1973. Before then, Yvon was making pitons for climbing which you’d hit into the wall, but he realised they left holes in the wall, so he created this idea of ‘clean climbing’ and changed his whole business around. And you still see that sort of thinking within the company. This is not Patagonia being responsible now because it’s a hot topic—years ago when it wasn’t a topic at all, Patagonia was figuring out how to make a fleece from PET bottles, and in ’92 we started looking at how all of our cotton could be organic, and by ‘96 everything was organic. There was no supply chain at that point, so Patagonia had to make the supply chain.

It almost seems like more of a long game—building a community.

We often say that this is an experiment in doing business differently, and we’re currently halfway through a 100 year experiment. Sometimes companies in the outdoor world do work on a conversion by conversion basis, but we want to take people with us. So if you buy a product from Patagonia, it’s my role to make sure you understand how the product is built, what it does, and where that one percent of the revenue goes too. That’s different from saying, “I make a black jacket, I want you to buy it.”

I think we always throw an extra bar up for the marketing we do. So that makes things more complicated, but more rewarding. So if you buy a jacket, we want to make sure you need it, and you buy it for the right reasons. And that’s how we communicate with the customer—that’s how we engage with you—that’s why we want you to repair your stuff—because that’s a long lasting relationship.

“This is an experiment in doing business differently, and we’re currently halfway through a 100 year experiment.”

Authenticity is super-important—we’re not perfect, but we’re transparent. If you go on our website you can find where our products are built, and how they’re built—we’re just trying to be transparent in what we’re doing, and I think people appreciate that.

People like honesty.

Yeah—I’ve worked for many brands, and they were all brands that people liked, but when I started working for Patagonia, people would grab me and say, “I LOVE THAT BRAND!” If you understand a brand better and can be part of their community, that can be really fun.

As a brand that’s often forging its own path, can it sometimes be difficult to implement these new ideas?

In ’96 when Patagonia moved to organic cotton, only one percent of all cotton worldwide was organic. And now, 26 years later, still just one percent of cotton worldwide is organic. Of course we consume more clothes, so there is more organic cotton—but percentage wise it has stayed the same, and that’s pretty frustrating. But then on the other hand it’s the good fight—there’s more and more people who love Patagonia and support us in our enviro-campaigns that we run, and it’s all worth the frustration.

There are great examples of smaller brands who come in who do things responsibly—and great examples of bigger brands who want to go in the right direction—so if we can be the beacon of hope, then that’s good.

There’s success in terms of business and profit, but there’s also being successful in terms of influence.

That’s a great thing—like the way we built a wetsuit from Yulex. After we did that more and more surf brands started making their wetsuits from Yulex. And whilst one side to look at it would be, “Oh, our competitors are copying us,” that’s not how we think here—we’re high-fiving if another brand starts making a Yulex wetsuit, because that means fewer neoprene wetsuits.

And that’s the same with Walmart looking into Regenerative Organic agriculture—if a big organisation like Walmart wants to look at that, and wants to co-sign something which puts pressure on governments to make legislation, that’s a good thing—that’s what we need in the world right now. We need more and more companies to come on board—we shouldn’t just look at each other as competitors, let’s all do this.

On the subject of the campaigns you support, how do you pick them? There are so many different sides of every story—can it be hard sometimes to find the right angle? Not everything is black and white.

Finding the right angle and the right way to tell a story is really challenging, as is deciding which project to support, but actually finding the projects isn’t that hard. We have a few focus areas which are really important for the company, and through our One Percent for the Planet funding and Patagonia Action Works program where we promote all these different grassroots NGOs, often what happens is we’ll see a certain amount of requests coming in from these NGOs.

That’s what happened in the Balkans—we started seeing all these requests coming in from there, and then we found out that more than 3,400 dams were being proposed, and all these different local groups, from Albania to Bosnia & Herzegovina were fighting them. We thought, “This needs more attention,” so we started working with those groups to help amplify their voice, and one of the things we saw was that a lot of the funding from the dam projects came from a European bank—the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development—so we built a campaign to put pressure on them to change their policies.

And that’s how we work on these projects—it was the same with community energy. That’s a movement that’s happening right now—in Holland all of the legislation is in place, but it’s not in place yet in the UK.

Can you explain what community energy is?

It means community-owned energy. You have a roof above your head… schools have roofs… farm-houses have roofs… and you can put solar panels on all those. There are all these different projects where the community comes together to start an energy project which could for instance give energy to the whole neighbourhood. There’s a great example here in Holland where the community on a small island put solar panels on their roofs, and got their energy through that. And then through the profit they earned through that, they bought cars and electric bikes…

So they become their own energy company?

Yeah—and the main thing is that we have loads of roofs and space where we can produce energy.

This decentralisation idea seems to be very important at the moment—as with regenerative agriculture it feels like this shift from the mono-culture to more community-based projects is where the interesting ideas lie.

Quite often, but it does depend on how the organisations are set-up. There are great examples of bigger organisations that do work really well, but at the end of the day, communities are super important. Community energy is a great example where a community can actually lead the way in things, but some sort of stuff needs bigger organisations involved. If you look at all the issues we have in the world, a lot of them are because of this globalisation—and it’s not that globalisation is necessarily a bad thing, but it’s just that it went sort of out of control.

With Patagonia now reaching so many people, can it be a challenge to communicate with them all?

It’s a fun challenge, but there are more similarities than differences. We made a film around a trail runner from London running the length of the Thames, and of course trail running in London is completely different to somewhere in the mountains, or even here in the woods near where I live, but there are so many similarities between these communities and what they care about, that you’ll always find common ground and common stories.

At the end of the day if you bring people together who are into the same things, they’re interested in the same topics—community energy in Manchester might be different to community energy in Holland, but people will still relate to the idea of it.

Wherever you are in the world, you can relate to someone’s struggle or their passion.

Yeah—and what’s super important is to bring positive story telling. We need to address challenges we have in the world, but for most of the issues we talk about, there are so many positive solutions and stories.

No one wants to be bummed out I suppose.

You still need to wake people up to certain things—if you watch our film about lift-expansion in the Alps there’s a bit which bums people out because people love to ski in these huge resorts, but if you dive deeper there is a positive story in there—you can change things. There are so many unbelievable, inspiring people around, so it’s a case of bringing the conversation to the next level. We did a film about a non-binary climber, and it was great to bring something like that to a community that isn’t used to these conversations.

Does the outdoor industry need to catch up a little with some of these things? Going back it’s been a very upper-class world.

Yeah—I would say that the world as a whole isn’t there, and the outdoor industry isn’t there either. There are really good initiatives and great things happening, but we’re not even close yet. It’s all a journey and it’s super important that we’re now starting to work through a lot of these challenges.

A lot of companies look to Patagonia as inspiration, where does Patagonia look? Who inspires you?

I think the inspiration comes from the groups we support, and the work they do. Often it’s less hard to find inspiration because there are so many amazing people doing great work—so we want to celebrate their stories. Or there might be people who’ve worked with Patagonia on a new sort of fabric—that’s where I get my inspiration from—all of these different people we meet or work with.

At Patagonia it’s not about figuring out this beautiful sauce to make people want something, it’s more about figuring out how you tell a story the right way so people understand it.

I suppose being involved with so many different projects, there’s so much to talk about.

We’re not a trend company. If you look at our products, they don’t change a lot. Our Better Sweater has always been a Better Sweater, and that really helps—we can go on longer term story-telling.

Yes, we understand how people work and what tools people use, but we still make really long form content, because that’s the right way to tell a story. And that sometimes makes things hard because people just want everything fast.

There’s still a place for these longer articles… or considering how long this article will probably end up being, I hope there is.

Yeah, they’re important. Learning about dams in the Balkans—learning why dams are bad, and even learning where the Balkans are… explaining all those different things required long term storytelling in the right engaging way. That doesn’t mean we don’t use social media, but it means we look at what we need to say, and how we can say it.

That makes sense—using the right tool for the job. I know you’ve got another meeting now so I’ll let you get off—have you got any wise words to end this with?

I watched the film Belfast recently, and there was a quote in there, “Be good, and if you can’t be good, be careful.” And I think that applies to Patagonia—we’re trying to be good, but sometimes it’s about being out there and being on the street supporting all those different groups. We all need to show up, because the issues are big and we can all use our voice to make a change, because all of the solutions are there. Don’t get trapped in the negative.