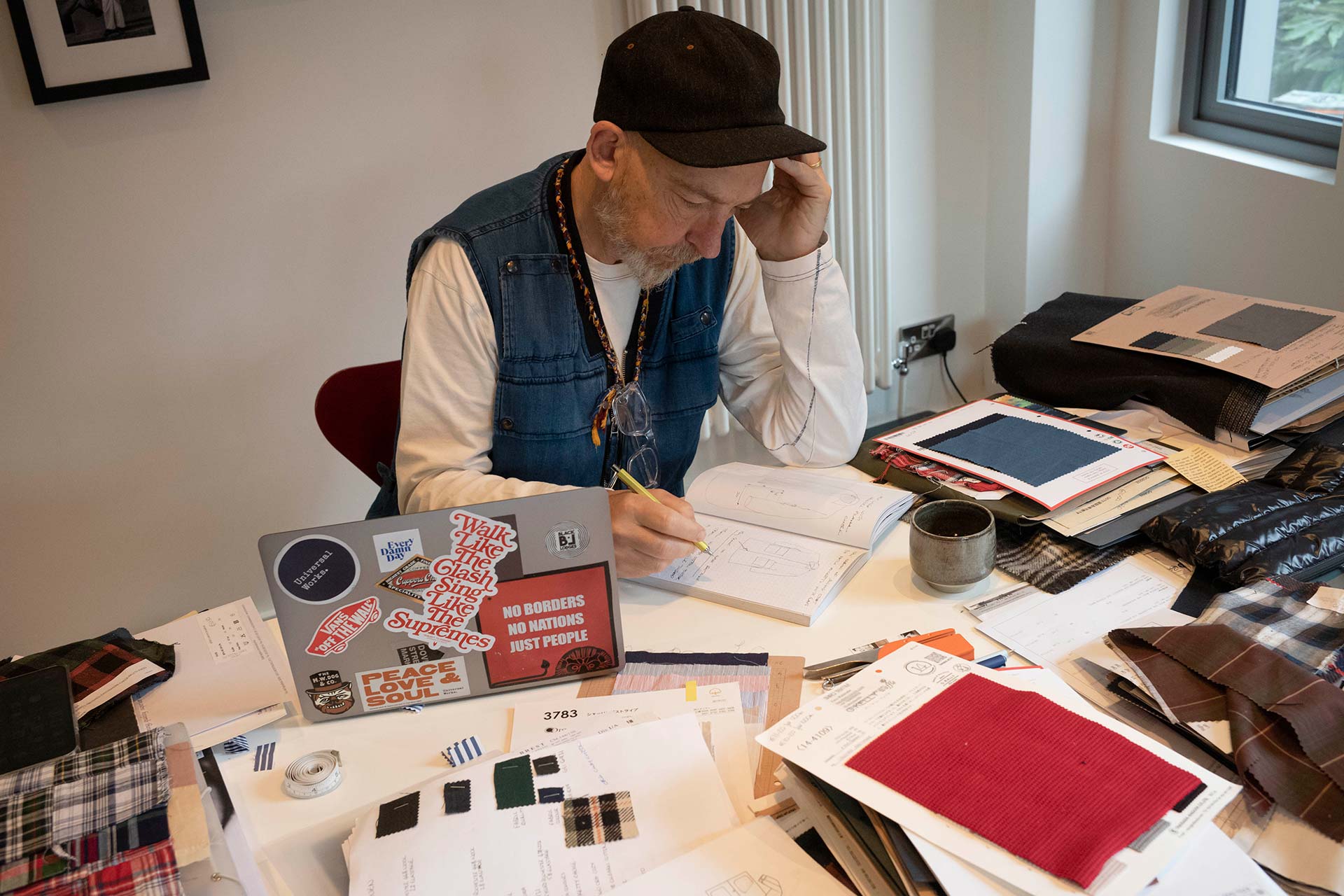

An Interview with David Keyte, Universal Works Co-Founder

An in-depth conversation with the menswear designer

Founded in 2008 by David Keyte and Stephanie Porritt, Universal Works takes cues from sportswear, functional military design, utilitarian work-wear, British tailoring and about a thousand other reference points, to make a range of modern, wearable clothing.

In today’s fractured age—an amped-up era when everything at once vies for your attention, Universal Works has made a name for itself off the back of well-thought-out design—free from gimmicks, but rich in functional details.

In this extensive conversation we talked to David about the early days of the brand, separating business from creativity and the importance of mixing things up…

How has running a clothing company changed since you started Universal Works? 2008 doesn’t sound that long ago, but things move fast these days.

Certainly by then there were people trying to—and succeeding—in being direct-to-consumer. That was a new route for clothing companies, and before that, the only way to get to market was to sell to the retail trade, or to open physical stores.

So for us, we could go to a bunch of retailers and sell a product—and then make the product that we had sold—so we’d sort of pre-sold it, if you want. In a way, it’s a relatively green model, because you’re only making what you’ve sold. Obviously those stores still have to sell it, but we’re not making lots of waste.

I might be wrong, but it always felt like the brand came from the idea of ‘what makes a good jacket?’, rather than ‘what will people buy?’. That seems like an important distinction when starting a clothing company.

Yeah, I spent my life obsessed with that question of ‘what makes a good jacket’—that’s what I wanted to do. And I thought that if I spent enough time making the right jacket, and got someone to buy it, then I’d eventually be able to pay the mortgage—but that was the secondary part of just wanting to make a great jacket. If not enough people bought it, then at least I’d have tried and had a go at making a great jacket. It wasn’t about having a go at making a lot of money.

And it sounds a bit la-di-da and romantic, but I wanted to make things that I wanted, and I thought that people might be interested. It was the product that was important—and if we sold it to shops, we’d figure out how to make it, and how to pay for it, before we got paid.

My mantra back then was to not have a plan, and just do what I wanted to do, because I believed in the product, and I believed people would be interested in it. And when I say I didn’t have a plan, the plan was to make great things that people might want to buy, and then hopefully I could make more great things, because I’d have some profit—but there wasn’t a plan in the sense of “after five years, we need to be this size, and then we’ll get this investment.” There wasn’t a financial route we were trying to find, I just wanted to do interesting things, and part of that would take me to interesting places, to meet interesting people.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Was there a point where you felt people started to get what Universal Works was about?

I guess when you first achieve certain things, like making a good coat, then you want the world to see it, and believe in it with you. Oi Polloi bought our very first collection, and I was in heaven because I so respected what they were doing at the time in terms of clothing and how to present that to the world, and they’ve bought every collection since. And that still humbles me.

And they’ve got more opinions there than half of the world—wrapped up in two blokes—but I totally love the fact they’ve got opinions, and they still come and buy our product. They’ll still say, “Can we have that in a different colour… or can we have this…”

Haha… from working there for a good number of years I know from experience they won’t make it easy for you.

No, and I love that of them, and that should never change. But to answer your question, I don’t think there’s ever a point where you think, “We’ve kind of made it now.” Honestly, I absolutely shit myself on the first day of sales every season. I’m a total wreck, because I assume that no one will like it, no one will buy it, and then how am I going to keep 40 people in a job?

Is that a good thing though? I’m not saying it’s good that you’re a total wreck—but does it show you still care and aren’t getting too comfortable?

I don’t know if it’s something I can consciously change, because your level of personal confidence comes from how you were maybe when you’re five or six years old. You definitely can get more confidence the more success you have, and I think we’re confident that as a business we’re doing good things, and we’re doing it the right way—but on a personal level, because I’m responsible for say, that four-pocket parka, then if people don’t like it then it’s my fault, and everyone else’s mortgage is relying on it. It kind of comes with a different level of stress.

But I think it’s good because you’re not getting carried away. It’d be for other people to say whether I’ve changed as we’ve become more successful, because you don’t see it in yourself. But yeah, I still get very nervous.

“My mantra back then was to not have a plan, and just do what I wanted to do, because I believed in the product, and I believed people would be interested in it.”

Sometimes it seems company owners reach a certain point and the effort slows down—they rest on their laurels, and that’s usually when the character gets lost. But that’s not happened with you.

Yeah, I think when we started the business, we tried very hard for it to be this thing called Universal Works, that wasn’t about me or Stephanie—my business partner and life partner. It wasn’t about us—it could have been anyone, but then people started wanting to know more about us, and wanted to interview us. I’d think, “No, it’s Universal Works, not David Keyte,” but people do want to know about the human beings behind it.

And I think that was something I felt was slightly newer—that newer audience wanted to feel like they were part of something. We started talking about community in a way I’d never heard used before for clothing. I understood community because I came from a council estate when a working class community was a community—you did things for each other and with each other.

I think as we’ve started to lose local communities, people have grabbed onto communities that they’ve discovered through Instagram—and even if it’s from something like that, it’s still a community. People are interested in the same things, they’re wanting to talk to each other about the things they’re interested in. And that was something new for us—so we had to embrace it. And in a way I think that helped Universal Works become more interesting to that community—they could see I was the same as them—I wasn’t trying to force something from above. I’ve got the same interest in the same things, so people can relate to me—and to the garments, hopefully.

So I think it does become harder for it not to become personal, but in a way, that’s been part of its success. Who you see is really us—we’re not trying to be something.

It’s not men in suits trying to pretend it’s some independent brand.

Yeah—and I think perhaps the level of confidence you have to have to be able to be yourself and do whatever you want to do—people see that—they see the guy out there doing it… but most of the time I think it’s all going to fall apart tomorrow.

Almost like impostor syndrome?

That’s it. I’ve got that with buckets and spades. How can anybody have let me get to this point? Someone asked me to talk about how to get a successful business in America, and I’m thinking, “You’re definitely asking the wrong guy.” But then in their world, maybe having the number of customers we’ve got, and the level of sales that we’ve got over there, is huge success? Even if in the real world, it’s tiny, but in our little community, the fact that we’ve got 35 stockists in America is brilliant. So people do want to know, and they do see you as an expert. And in reality, most of it is just turning up.

My favourite bit of advice to anyone is just to keep turning up, because most people just talk about it. So we do our best to make a product that we believe in and people are interested in, but then you’ve got to actually make it, and deliver it, at the right price, with the right quality, so a shop can sell—and then you’ve got to do it the next time, and the next time, and the next time. You’ve got to do it when no one’s looking too—that’s the thing.

There’s clearly a huge amount of work in running a business like this—but what’s your process when it comes to the actual design part of it? Do you need to shut yourself off from the more ‘business’ side of things for a while?

Yeah, and I guess I do think of it as a different ‘hat’—like I need to go and be creative. Of course, it’s menswear, and it’s relatively commercial—we’re not reinventing the wheel, so some of that creativity comes with a sense of business—I need to have enough sweatshirts, and I need to have enough shirts, because they’re big areas for us, so I need to make sure there are enough products there.

But also, from a creative point of view, you need to stick your neck out, and go for it. Otherwise, you become boring. So that’s why trying to separate the business side sometimes is important—to let the creative side of it work.

I’ve said it a lot, but if you’re just creative, making amazing things that you don’t have to sell, then that’s art. And there’s a huge place and a need for art in our world—but we need to get paid. It’s a business, so we can’t kid ourselves that we’re artists—we’re making a product that people want to buy, we need to make a profit out of selling it, and then we get some money.

So we have to do all the business side of it, and if we can’t make that work, then we don’t design it. If your shirt factory can’t put four pockets on a shirt, don’t design a shirt with four pockets, as you’re asking for trouble. So I’ve always tried to design new things in terms of the person who’s going to make it. Because my background is in making things.

You’ve got to be grounded in reality.

Yep. I’ve wanted to make a really great seam-sealed jacket since the birth of Universal Works, and I didn’t do it until this year because I didn’t have anyone to do it at a price-point I thought I could sell it at. I knew what I wanted, but I needed to find someone to make it at the level that we could then administer. So the creative side is definitely a different head, but in all honesty, I’m not sat here drawing marvellous Cecil Beaton style drawings in my atelier—I’m thinking about, “Is that shirt-sleeve too long? I’ll ring up the factory and tell them now.” It’s much more practical.

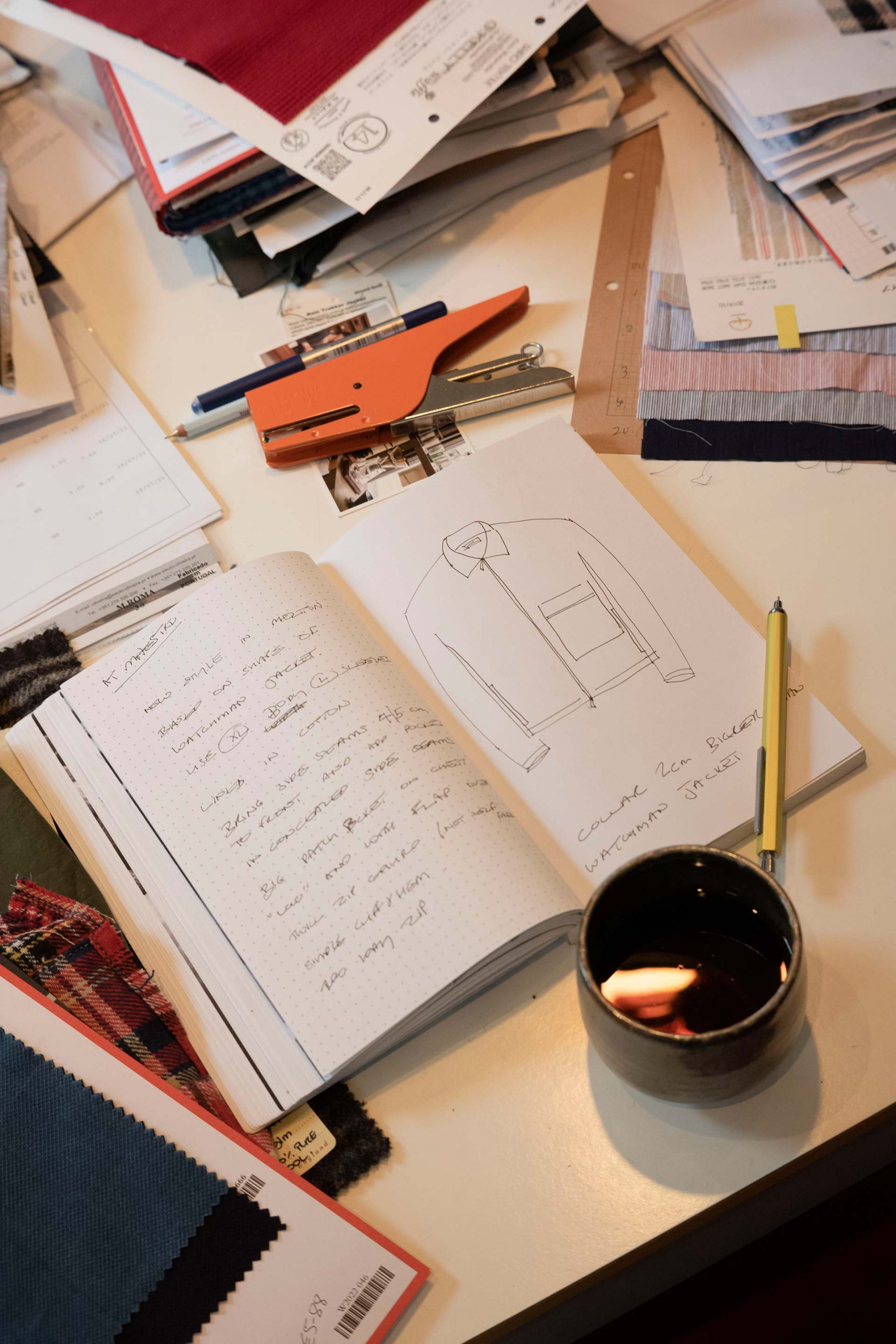

Half of it is done with little sketches and drawings in a notebook, sending iPhone snaps to a sample room somewhere, and with them knowing me for 20 years they’ll think, “I know what he wants.” Then we’ll get it half right—and this can be in Nottingham or in Portugal or in India, and they’re all happening at the same time simultaneously. So part of it is a spreadsheet, and part of it is a little sketch in a book and some bits of fabric, and somehow it all comes together, just because I’ve done it for so long. It can be unbelievably romantic, and then unbelievably not—in the same breath. I could sit down drawing my little sketches all day—but I can’t do that, I’m not that person, and I don’t have the team around me to do that.

You can’t just be some tortured artist.

You can—but I don’t think I can. There are other brands that I have massive admiration for, which have a design team, and then other teams for different things—but it just wasn’t how we began. For the first four years it was two of us and a bookkeeper. And as you build that up, we’re still building that, we need to still build that. Sometimes I think Stephanie and I are the biggest problem in the business, because there’s too much going through us.

If you started something from the ground up, I imagine it’s hard to let go of certain aspects—you’ll always want to know what’s going on.

Yeah—it’s interesting. I read something the other day—it was about how to be a good business. It wasn’t written by the guy who started Patagonia, but it was written by one of the guys who joined it early on. He was talking about the success of Patagonia—the things they got right, and the things they got wrong. And he listed the principles to follow—one of which was to give ownership to your staff, but then he said, “In reality, we’ve never done that, because the people who started it still own it all because they figure if they give the ownership away, the staff will become risk averse.”

Because they’ll suddenly have the responsibility?

Yeah—and also, they’d be like, “Well, I’m doing alright now, I don’t want to mess it up—so let’s not do that new crazy thing, because it might not work.” Whereas actually for Stephanie and I, this is our life—we’ve got the responsibility of lots of people who now work with us, and we want to get it right, so yes, there’s pressure with that. But also, if we make less money next year, we won’t go out of business—but we wouldn’t be able to pay the shareholders… but do you know what? There isn’t any. So who cares?

So if we do something that doesn’t do that, or just isn’t as monetarily successful—like saying, “Let’s open a shop in Berlin,” which we did—it might not work, and we might lose €100,000 but it won’t put us out of business. But it would mean the directors don’t get paid €100,000, but that’s us, so it’s fine. Of course who doesn’t want to be more successful, but I’d rather have the opportunity of opening a shop in Berlin, and seeing if it works, because that’s exciting and fun.

There’s been a big shift to direct-to-consumer brands lately—but is there still a need for these interesting multi-brand places?

I think so. The new, interesting, innovative people doing things that you want to see—they need a multi-brand store to get their product out there. How do they do it otherwise? And yes, I know we all have access to every market now because we can open a shop online, but without the ability to push yourself up the list at Google, it’s really hard. Whereas, with an independent store, it becomes part of something in their community—Oi Polloi in Manchester is an institution. People in Manchester know it—and if you’re interested in that thing, you go there because there’ll be something new to see.

There’s a bit of kudos with getting into these places isn’t there? If a cool shop starts stocking something new, people take notice.

It’s a bit like the supermarket gives you a huge amount of choice, but the reality of life is that there’s less choice now there’s lots of supermarkets. They guide you to what’s on the eye-level shelf—and it’s all about maximising their profit. There’s no sense of community and no sense of value to their customer—even though that’s all they talk about—it’s actually about profit for their shareholders. And it has to be—that’s your legal responsibility as a corporate shareholder—you have to make money for your shareholders.

“Some of the most exciting things come about when you take something traditional, and turn it into something else.”

Whereas the little corner shop can be as altruistic as it wants to be. It can say, “I know Mrs Smith hasn’t got any money, but we’ll let her have her groceries this week.” And not only is that not going to happen in Tesco’s, it’s illegal—it’s written in their reason for being. Whereas I want someone who says, “You know what? Mrs Smith is going to starve if I don’t give her that food, so I’m going to give it to her.” They know they’ll make enough money out of Mr Jones and Mrs Baker that they can let Mrs Smith have a week’s free groceries. That matters in life, and therefore I want those little shops to continue.

And I like the fact that these little shops give people the chance to have a go—you can open a store in Bolton—somewhere far enough away from other stores to have a chance. And that’s exciting—and that’s how you get new things. So I think independent multi-brand stores are really important—I love them. If we’re not careful we end up everything being very monotone—everyone reads the same newspaper, everyone shops at the same place—it’s not good for us as human beings.

There needs to be a mix.

And I think part of that is that those shops can take risks—and they sort of have to. I love Stussy and Carhartt, but If you’ve only got Stussy and Carhartt in your shop, why is anyone going to come to you? They can buy it everywhere. But if you’ve got two other really cool interesting things—and you have Stussy and Carhartt, then I might come to your store. You’ve got to have an attitude. Oi Polloi always had some weird shoe, or some crazy colour—even if they had the same brands, it didn’t look the same.

There’s individual character there.

Yeah, and that’s what I love about shops like that. Sometimes I can walk into a stockist of ours, and it can look like some sort of theatre-land, all outrageous, and then someone else can make it look really macho. I like the fact that different people can make it look different. That’s when you’ve got an interesting shop.

You were saying before about how when you’re designing clothes you’re thinking with production in mind—but even still, a lot of your designs blur the boundaries. You make cardigans out of fleece… or suits to be worn casually… is that mixing of styles an intentional thing?

Yes, absolutely. I guess my clothing roots started in culture or cults—whether that was Northern soul, or punk or rave, and whilst there were formal suits and formal shirts, for me, I liked the fact that if you mixed it all up, you could wear really normal things, without looking like anyone else. Someone wearing a suit jacket with a pair of jeans, or wearing a smart suit with trainers, or wearing jeans with formal shoes—and that sounds so innocuous now, but back then no one did it—you were weird. Just putting one thing there that wasn’t right. And that, to me, was the best thing. It was that mixing of things that were wrong that made something interesting.

I was lucky enough to go to Japan on business and I saw a lot of the Japanese designers taking elements of formal wear or sportswear or military things, and completely messing with them. So you could have an M65 jacket, but with frills on it. And yeah, I wasn’t wearing it—but I was being completely amazed by it. I thought, ‘I love this idea—so we should be able to do that too—we should be able to mix those things’.

So yeah, it’s 100% intentional, and the idea of being able to wear a more relaxed thing in formal situations has also become quite normal, and has been speeded up dramatically by what’s happened in the last two years. So you can wear a much more informal suit to a formal occasion now—you won’t offend anyone because it looks right enough, but actually you feel kind of cool and comfortable in it—and you can wear it afterwards.

It’s not some weird shiny jacket you just wear once.

Yeah, and you can put something on that feels like a sweatshirt, but you can wear it in the office. You can feel like you’re not just dressing down—you’re slightly dressing up. And we need more of that—dressing up is fun.

Even now, years after these movements like punk or rave that supposedly changed things, we’re still pretty strict.

As a species we’re inherently conservative—with a very small ‘c’. We inherently don’t like change. It can be hard for us to not look like everyone in the pub can’t it? We get a little bit nervous of looking or sounding different sometimes. And also, I think we still get guided by popular culture—whether that’s TV or radio or press. Even though we’ve got access to everything online, so many of us are being shown the same images that we think are the norm.

It’s hard to break past that. Now there’s the potential to dig deep, searching out films that were once really hard to find—but most people are just scrolling through Netflix watching the same thing.

Because most of us want an easy answer, and an easy life—and understandably, a lot of the time. And there’s nothing wrong with that—why have a complicated life, if you don’t have to? But yeah, I think a bit more individualism should be supported. I think things have moved on and changed a bit though—and one of the great things about Britain is that as much as there’s an awful lot of intolerance around, we’re a tolerant nation when compared with many. You can have weird hair or weird clothes, and people aren’t throwing you out of the pub, are they?

We’ve got the freedom to wear a fleece cardigan without oppression.

Yeah, in the last couple of winters our best selling item was our fleece cardigan. It’s actually more like a jacket made out of a mountaineer’s fabric, but I laughingly call it a cardigan because no one wanted to buy a cardigan off me. And we’re astonished by the success of it, because it is an unusual item—it’s not quite any of those things. And that, for me, is great. The fact that it’s almost ten other things means it’s almost its own thing.

Maybe that’s like how the best music or the best films are usually the product of a few things being clashed together—when a band takes another genre and mixes it with something completely different is usually when something interesting happens. Or when one subculture takes hold of something from another one…

That’s really true—that’s a good point. Some of the most exciting things come about when you take something traditional, and turn it into something else. Whether you’re the Beatles stealing rock ’n’ roll, or some hip hop star stealing a relatively banal soul track and turning it into something much more streetwise, it’s changing things, it’s mixing things up. And that’s where some of the best things come from.

Is it a case of having the confidence to kill a few sacred cows every now and again? I suppose you were talking about being nervous or lacking confidence before, but you don’t seem to let these design conventions hold you back.

In terms of those things, I dive in head first. “What can I make this very formal fabric into that you wouldn’t expect?” “Can I make that military jacket out of soft wool? Because that’ll be interesting, won’t it? So I start off with that, for sure.

And that’s surely more interesting than just recreating the same old jacket.

For me it’s just a big wardrobe. I just get excited by a nice new thing. I’ve got a four-pocket parka, so I need to get excited by something new.

Haha, that makes sense. We’ve been chatting for a good while now so I’ll try and wrap this up. Have you got any wise words to end this with?

I don’t know—there are a lot cleverer people that should have the right to be profound more than I do, but in terms of the business and what we do, and I think the only thing I’d say would be that trying to not conform is much more exciting that just doing what everyone else is doing. Mix it up and bend it around… do something else. And then just turn up. And do it again. It’s hard work, but if you enjoy it, you’ll want to do it, and keep doing it.