An Interview with Dave Dye

An in-depth conversation with the master ad-man and art director.

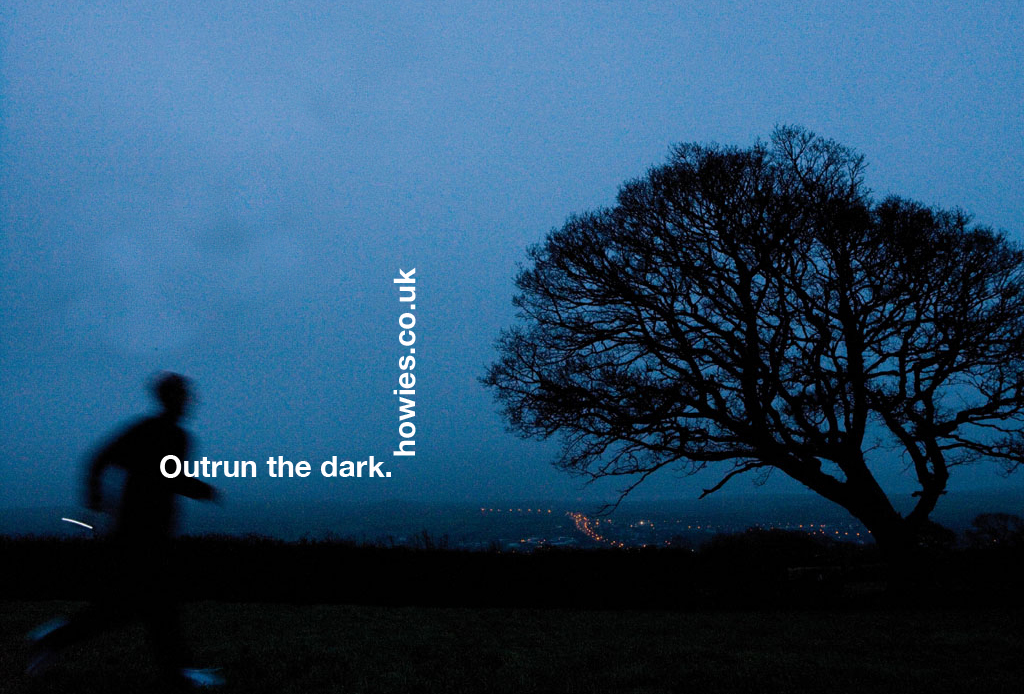

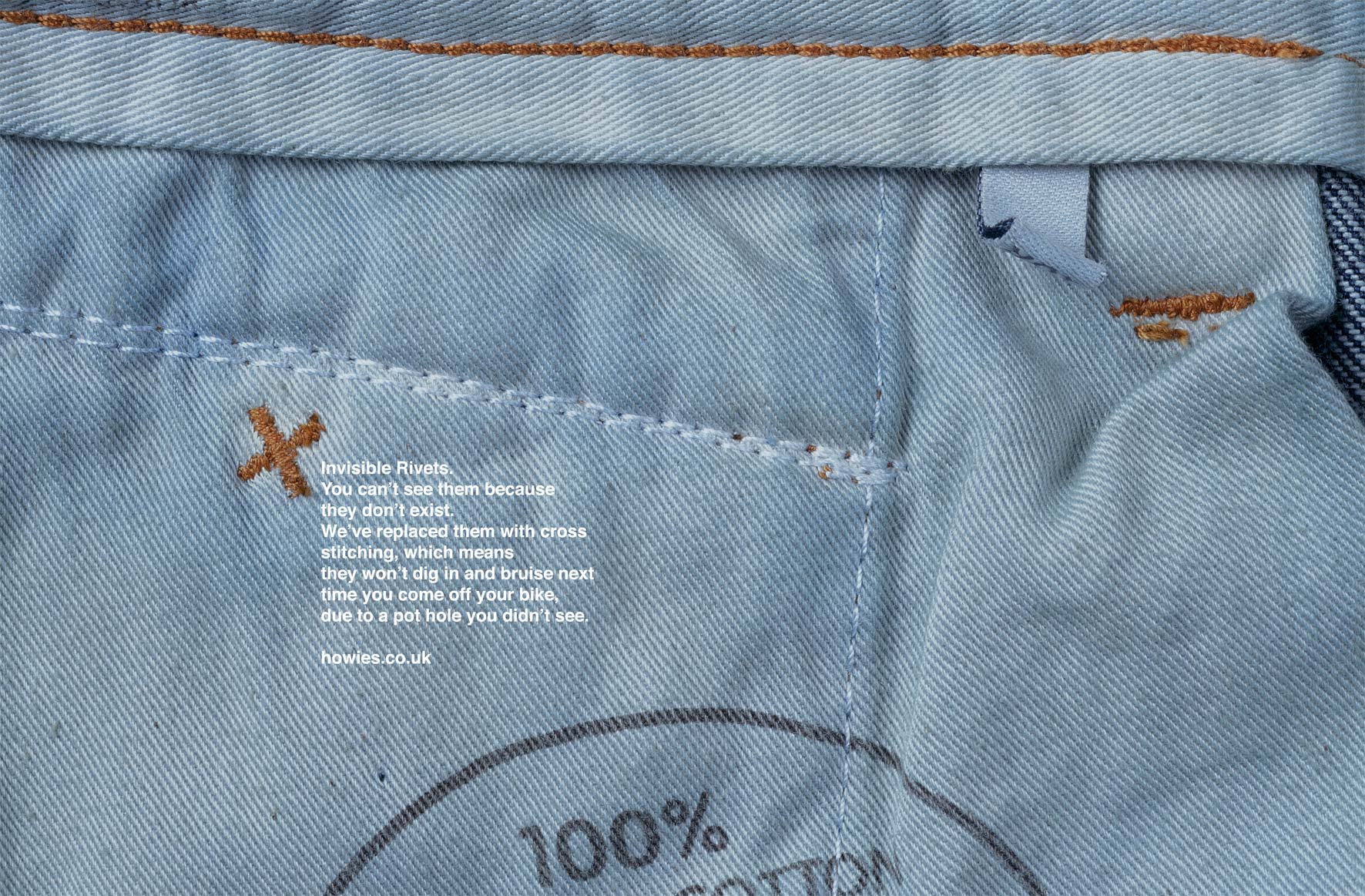

Every day our unsuspecting minds are peppered with thousands of adverts, but only a handful are any good. Since the mid-1980s, Dave Dye has been making what would sit firmly in the ‘good ads’ category—his work for brands like Howies, adidas and Mercedes avoiding the hard-sell in favour of sharp observations that don’t patronise the punter.

Beyond making adverts, he also plays a huge part in archiving them—and his Stuff From the Loft blog is a valuable mine of priceless visual ore, giving a glimpse at the work of countless forgotten or overlooked masters of the advertising realm.

In this extensive interview, we covered all-manner of ad-related subjects—from his early days sketching swimming hippos to his thoughts on today’s digital age.

Going back to the start, how did you get involved with advertising in the first place?

I got my first job in 1985, advertising was very glamorous and influential back then. It was before it was chasing you around the internet and driving people nuts. The main contact anyone would’ve had with it would be TV ads, which often made them laugh, so they’d talk about them at school or work. They liked it.

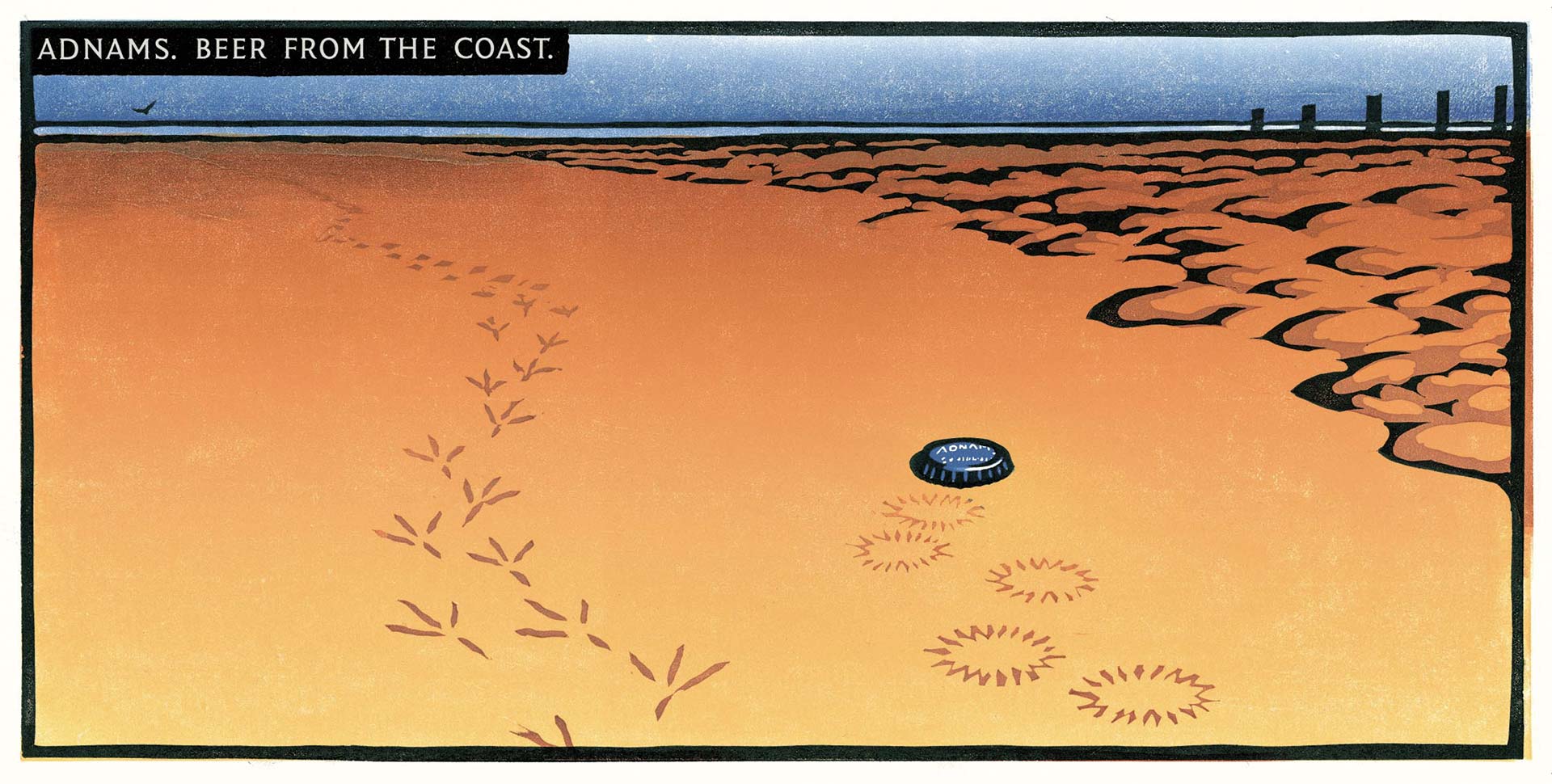

Not every ad was good, there was a lot of garbage too, but at their best they’d be like memes today—known, shared and enjoyed. At the time advertising agencies used the best directors, photographers and designers in the world; because they had tons of money. Posters like the Benson & Hedges ones were like art on the streets. They were amazing—not this ‘we’re awesome’ type guff—they were just a cool way of reminding you of their existence. They were intelligent, entertaining and seduced with their humour and creativity.

Anyway, at school I was good at drawing, so the job that kept being mentioned was Commercial Art—whatever that was? (It was probably a bit like design and a bit like illustration.) So I started off doing design, well, not true, I started by making tea in the offices of people who did design. That brought magazines like Creative Review and Direction to my attention, where I found out about advertising and how it worked. It looked great; dreaming up ideas that would end up on TV or 20 foot long on High Streets. I decided I’d try and get into that.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Was it easy to break into advertising at that time?

No, it was really hard. If you went to Art College at the time the only creative jobs people talked about were design or advertising. So there was a lot of competition, everyone was after them. Now there’s dozens of creative industries vying for creative people’s brains, so the competition for creative jobs in advertising is less, but that’s not to say it’s easy.

I didn’t know anyone in advertising or have any clue on how to go about getting a job in it. I’d draw some ideas for ads and then send them to people I didn’t know at places I thought were ad agencies. Some were, some weren’t, some were design companies, illustrators, P.R. agencies, I was clueless.

So you were creating imaginary adverts?

Yeah, I’d think, ‘I’ll do an ad for Durex’, for example. So I’d draw a dozen rabbits in a line looking at the camera and write underneath “The Smith family have never heard of Durex.” More of a cartoon than an ad, but I’d draw a logo in the corner, so it was an ad.

Then I’d think of one for Dulux paint, then Harp lager, no campaigns, just a stream of random ideas. I’d have to draw each by hand, colour them in and then send them off, I didn’t have a photocopier at home at the time—nobody did. It was a lot of time to invest in a letter to someone I didn’t know, maybe six, ten hours per letter, not surprisingly, very few people would reply. It was soul destroying.

Occasionally I’d get a polite letter from a secretary saying, “We’ll put you on file.” I was trying to improve, write better ads, but didn’t know anyone in the business, which would have been bloody helpful.

You were on the outside, looking in?

Totally, my letters were saying things like, “I’m really awesome, I work really hard, I’ll be great…” I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to write better ads, so I tried to write a better letter.

I sat down to write it and I realised that I didn’t know how to address the person—it might have been someone on the front of a magazine I’d seen, like John Webster, who was a big deal in our world. Should I start with “Dear Mr Webster”, “Dear John” or “Dear John Webster”? What’s the protocol?

So I had the idea to write every combination; start off really formal, “Dear Mr Webster Esquire…” cross it out, and get gradually more and more informal, ending on something like “Dear J-Boy, fancy a brew?” Suddenly I got lots of responses and interviews. Exactly the same work, different letter. That small thing of being a bit more human, more interesting and funny, led to me getting my first job.

What was it like once you’d made it in then? I was up in the middle of the night recently and I caught that film, How to Get Ahead in Advertising, from the mid-80s. Talking boils aside, was that an accurate depiction of the ad world back then?

Yeah, at that time it probably was a bit like that film–all Ferraris and lunches, but not for me, I would’ve been young, underpaid and overworked. Although I say underpaid, when I started, the salary for a grad in advertising was the same as a grad in a law firm—that’s a good indication of how highly advertising was seen back then. Advertising was seen as an opportunity for companies to transform their businesses, whereas now I think it’s seen as something they do reluctantly, hoping for a 0.5% uplift from a digital campaign.

Just ticking a box?

Kind of. Digital has changed things. Any growth is good, obviously, but people seem happy at such minuscule increments of growth.

Was there more of a captive audience back then? Things are very divided now, but only having two advertising TV channels and no internet must have meant a lot of people were sitting there doing the same thing at the same time.

Exactly. Today it’s hard to imagine everyone watching the same programme… and talking about it the next day. Occasionally it happens. Everyone appears to have watched Squid Game, but there are very few shared experiences. Everything is much more fragmented, with much smaller pockets of people dotted all over the place, so things are a bit more complicated, but the rules are still the same—you’re still trying to stand out and engage with people—the best ads do anyway.

Did the more concentrated nature of media back then mean advertisers would put more effort into things?

There used to be four ways of getting your message to people—TV, press, posters and radio, and that was it, now there are maybe 15 or 20. Which isn’t a problem in itself, the problem is that clients feel the need to participate in all of them, even if they have small budgets.

Rather than thinking ‘We haven’t got much money, so let’s own posters or make one great TV ad,’. It’s like gunpowder; you can divide it into 10 little piles or push it altogether in one big pile, the goal is to make a noise, get noticed, not to create as many rinky-dink little, low-budget bits of marketing (that people don’t recall seeing). Or to put it more eloquently, “People don’t remember the number of times you run an ad, just the impression it made.” That was Bill Bernbach, ages ago.

People see around 2500 advertising messages a day—on their phones, computers, TVs, streets, etc. Whenever I meet clients, I ask, “Seen any ads today?” 100% of the time they say, “No… I can’t think of any.” I point out that it’s 4 o’clock, so they’ve likely seen 1500, by companies who’ve paid to get in front of them and got nothing for it. Cut through is everything.

Going back to your early days, what was the first thing you worked on that you were pleased with? When did you think you were starting to do good adverts?

In my first couple of months in the business I did a TV ad for Hippopotamousse, it was on national TV, which was amazing to me.

What was that? A blancmange-type pudding thing?

Yeah, it was a pink mousse for kids, probably jam packed with e-numbers. The ad was like Fantasia, all the hippos were synchronised swimming. I had no idea how you did an ad, I just thought it’d be interesting to watch. I’d sort of half remembered this thing, everything wasn’t so readily available—you couldn’t access old films and TV like you can today. In retrospect it was a complete rip-off—I didn’t bring much to the party.

I suppose remembering things is a skill in itself in that situation. I often think that when I watch early Simpsons episodes. They’re full of really niche references, but the writers wouldn’t be able to check things on a computer—they just knew that stuff—they must have been complete geniuses. So yeah—maybe referencing Fantasia back then was more difficult than it sounds.

Yeah. I presented all these drawings of hippos doing synchronised swimming, and my boss thought it looked funny—and he might not have ever seen Fantasia. So we did it, and I could say to all my friends that I’d made an advert on TV, which was cool.

Once you get the hang of it, the bar raises. Back then awards were the way creatives were judged (probably still is) so you’d try to win them. When you win some, the bar raises again, you aim higher, five instead of two, Gold instead of silver—you never think you’ve done what you wanted to do. I don’t think I ever had a fixed goal of what I wanted to do, other than create ads that people notice and like.

Obviously with an advert, you’re trying to raise awareness and sell stuff, but was there anything outside of those things that drove your ads? Were there other ideas you wanted to get into your adverts?

Yeah—the best people tend to bring a bit of themselves to their ads. Without sounding like a boy scout, I’m quite moral—I wouldn’t lie or deceive, I assume I’m talking to someone intelligent, with a sense of humour. Some people’s start-point is ‘they’re all idiots out there, so let’s just make sure we get the brand name over’. What’s the point in that?

If I create a TV ad, and it’s funny and it’s interesting to watch, then you might watch it a few times—and if you do that, you’ve got more chance of remembering what its message was.

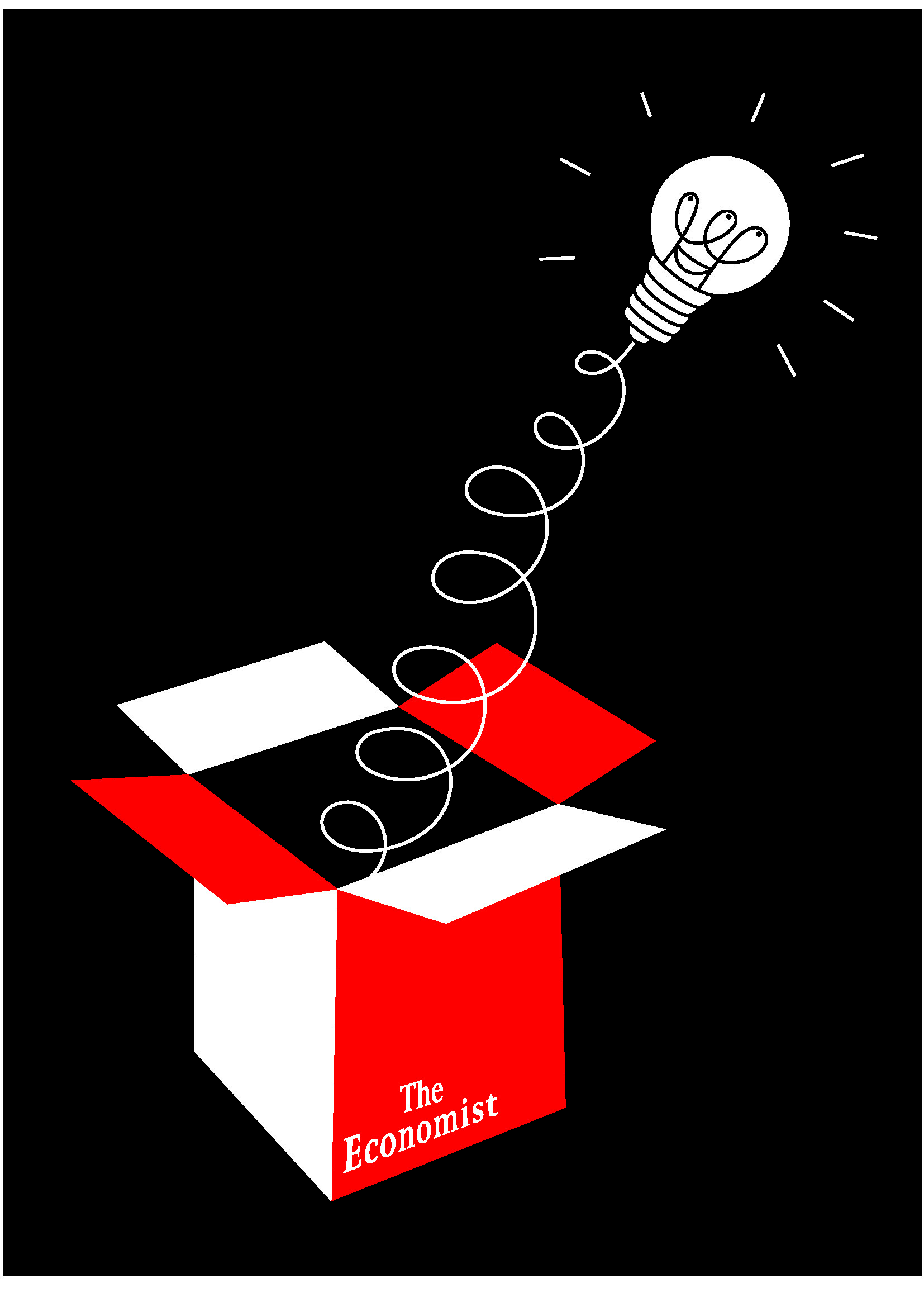

For example, I used to work on The Economist—which I loved. I could bring in observations on life, business and social situations—it was great. Like the poster, “The edge of a conversation—the loneliest place on earth.” Which I didn’t do, but love. A lot of posters up at the moment seem to be saying, “Try our new awesome drink. Look at these awesome models drinking it. Off you go.”

It also depends on what you’re working on, if it’s processed cheese your observations on life are less likely to be welcome. You sometimes read these articles where people assume advertising in some sort of mind-fuckery. As if you can manipulate people—but I don’t think you can.

Like there’s some sort of hacks or tricks to get people to buy things?

Most people ignore advertising, so you have to get under the radar by doing something interesting and engaging—and that’s not a subversive act. You’re just trying to engage with people, but being boring and dull will make people tune out. It’s not complicated.

It seems that although the channels of advertising have changed over the last 30 or so years, the core principles of good advertising have remained.

To me they have. The technology changes—where you see adverts or what you watch them on, but ultimately the goal is to create a good impression with the person at the other end of the tech. It’s a tube, it’s just how it gets there, it’s what you say when you arrive that’s important.

“Most people ignore advertising, so you have to get under the radar by doing something interesting and engaging—and that’s not a subversive act.”

Be it a printed poster or an Instagram post, I’m still thinking, ‘What would make them consider this product?’ What’s the little bridge between the product and the person? And once you figure out what that is, you then think about how you can do it in a way that they’d like… and find interesting. And that’s it, really.

In any channel or category, people say it’s specialist, like B2B advertising is different, but it’s not. It’s human beings. It’s the same stuff. People try and complicate it because it suits their agenda.

There are a lot of jobs involved in complicating things.

Of course, and people do very well by complicating things, saying to clients they’ve got these secret black boxes. Bullshit.

Does technology cloud some of this stuff a bit? It’s easy to be wowed by a gimmick.

When digital got going, in the early 2000s, there was a whole bunch of people saying how all the stuff that came before was ‘traditional’, and therefore rubbish and it was going to die. Lots of people adopted that view because it seemed cool, modern and forward-facing. It made sense—but it turned out not to be true. People are on their phones and computers more than ever, but generally, nobody likes, remembers or talks about a great banner ad.

Whatever the big TV show is, that’s where you’re going to get the volume. Digital advertising gimmicks come and go, like QR codes—ads with QR codes were all the rage for about a year—as if it’s not bad enough having to watch the ad, now your phone can take you straight through to the website for the actual Yorkshire Puddings shown. These gimmicks are sold as the future of advertising, they’re new tools for advertising to use, not a replacement of it.

It’s maybe hard to gauge how well a print advert does, but the digital stuff is a lot more ‘numbers-based’.

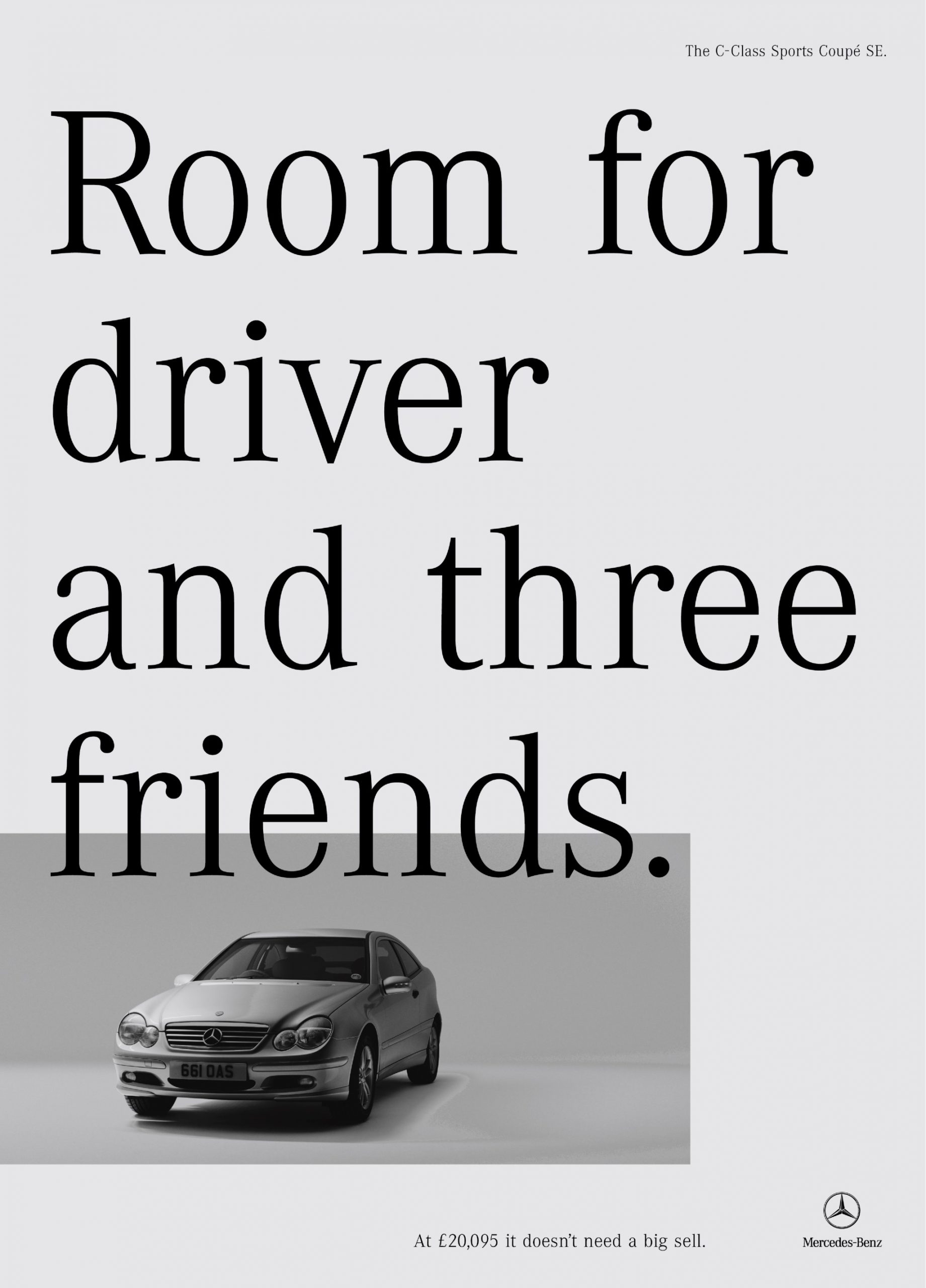

True. I did a poster campaign for Mercedes one summer, and they sold a shedload of cars. We went to a meeting thinking, ‘They’re not going to stop thanking us, we’ll be carried shoulder height through the company’ instead, they said, ‘Yeah, we did really well, but it’s difficult to know why that was—it’s been a hot summer, it is a convertible car, and it was a really good deal…’ They continued to list other possibilities as to why the car sold. At least with digital, credit is easy to attribute.

Do all these stats sometimes get in the way of good stuff?

Yeah—the top line for these things is always really impressive. I’m not sure what it’s like now, but I know with Facebook a few years ago the way they counted an engagement was something like if someone could cast their eyes on it for a second. That’s not really engagement, is it? Most of the measures for digital are generally things you wouldn’t get away with in other media, as they’re just too slight, if you know what I mean.

I interviewed a guy called Bob Hoffman, from San Francisco, who goes by the name of The Ad Contrarian—he’s dead smart, always calling out the bad behaviour of digital companies, like Facebook in relation to marketing. A couple of weeks before an ad popped up on Twitter suggesting asking me to advertise my feed, so I thought I’d see what happened if I went along with it, it’ll give me something to talk to Bob about.

I filled in all the forms and spent £100.

Two weeks later I woke up and at 7am there were 100 new followers. For me, that’s unusual. I thought, ‘Well, if I’m running these adverts for another two days, there’ll probably be another thousand by the time it ends.’ But by the time it had ended, it was still at 100. I don’t know what happened there, but it seemed weird that they’d all turn up at the same time, so I looked at the followers—and my blog is about advertising, and it has a certain audience—and they were all young guys in their 20s on beaches in South America.

That’s your key audience surely?

They didn’t look like the average ad dude. Maybe these guys necking beers on the beach liked old ads from the 80s? I don’t really know what happened there, but it didn’t smell good. But if you’re in a marketing department it’s win win. You can report to the board that you’ve increased your followers by X%, “Job done.” There are a lot of things that on a surface-level and in end of the year reviews look good, but don’t really help the company.

Does it prey on a lack of confidence from the brands? If they knew what they wanted, they wouldn’t be sold on this nonsense.

I don’t know. Someone called me the other day and said, “We want to brief you on a new campaign—we need fame.” It’s a funny business. There are very cast iron things in advertising that we know will help get adverts in the top percentile of what people will remember, and those kind of things are considered risky, which is a strange thing.

Simple—“Are we only saying that one thing?”

Unusual—“Feels a bit risky.”

Funny—“Seems a bit indulgent.”

It seems that brands often want notoriety, but they daren’t push the boat out to get it.

The irony is that if you make ads that cut through then people will notice it and therefore have an opinion on it. So clients will get more bad feedback, because people are noticing it. Sometimes people back themselves into running things that don’t stand out as much, because they don’t want to be in the spotlight—which is weird, because advertising is a spotlight.

Has it reverted back to the product—back to those old camera adverts in National Geographic which explain the product features in great detail?

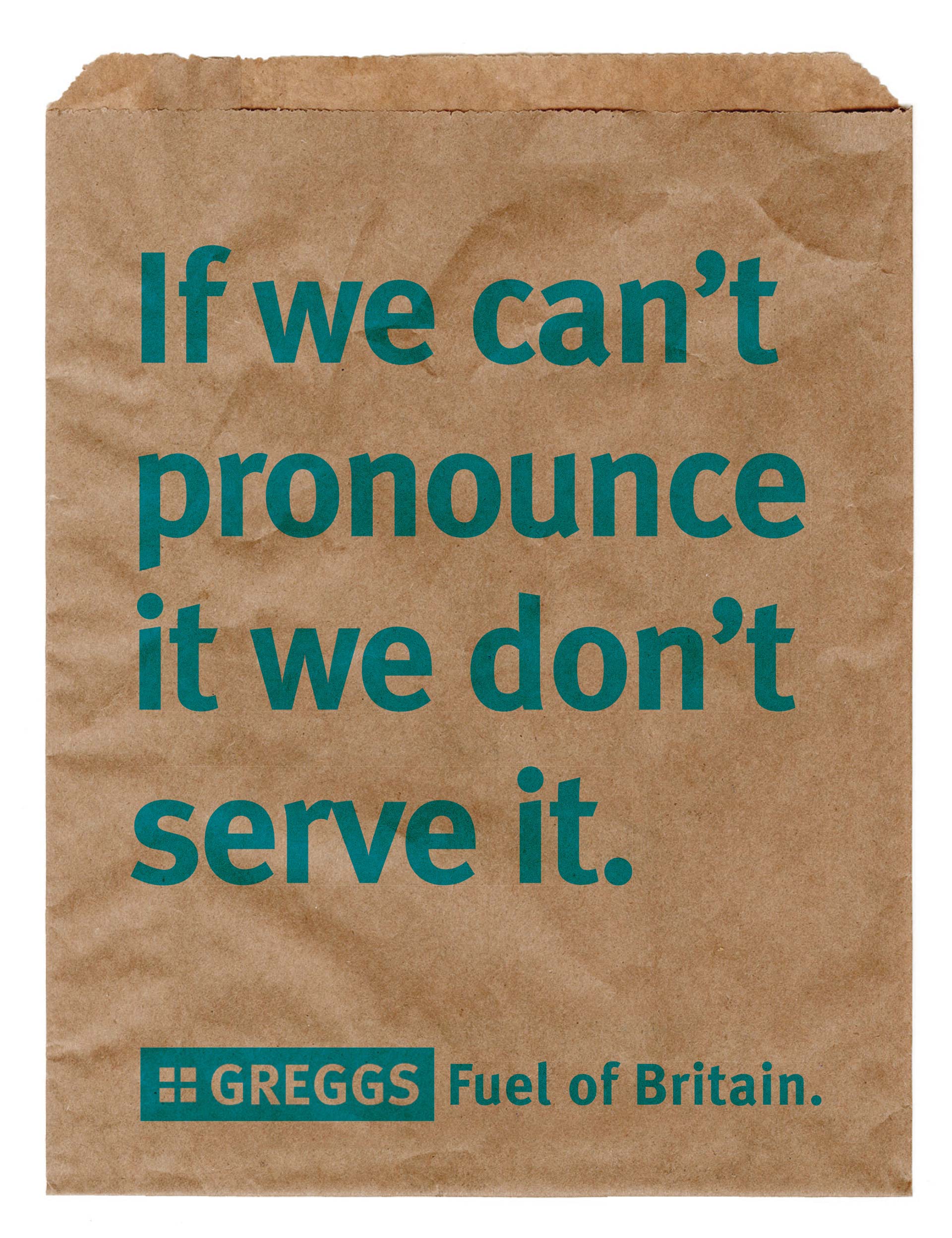

It’s become a dumber medium. I particularly hate all these word-salad brand lines “Find your happy.” What’s the one for Aperol Spritz? “Drink your joy.” It’s like they can only use the 50 most common words, so they just have to do their best.

It’s terrible. There was that one with Suggs a while back; “Let us quote you happy.”

Exactly. Sometimes things can appear fresh and unusual when you don’t follow the rules of grammar, like “Think different”. But mostly it just looks like pretentious rubbish to me. The rule I always use with students is, ‘imagine you saying this phrase to your friends’. If you feel awkward saying it to another human being don’t say it in an ad. You’re still saying it to a human being. Why people in the communication business think jumbling up words is a good thing I don’t know.

Looking at your adverts—whether it’s the adidas ones or the Mercedes ones—they’ve all got short, snappy messages. Did they ever try and tell you to get more technical stuff in there?

Always, yeah. Virtually always there’s a debate on making things more serious, or complicated. It’s a strange battle, because on the one hand it shouldn’t matter to me whether they run ads that are complicated or not, as long as I get paid… but it does. So you end up trying to persuade them to be really simple, or to say something in a humorous way, or to make the things look attractive, or whatever it may be—you have these debates.

And for me anyway, if I’m trying to make a point to you now, I’ll probably try and bring in an observation or humour—I wouldn’t try and con you, or talk down to you, because I’d lose you, but that’s what a lot of advertising does.

How did your website come about? It’s a solid archive of advertising through the years.

It wasn’t really planned or thought through. I had a domain and endless hard-drives of creative work. There’d be jpegs and scans that I could never find, so I thought if I dumped them all on a site, I’d be able to access them when needed. And in the process of organising that, I thought I might as well write what happened, explain why there are six different rough campaigns for Punch magazine. Having done that, I thought I might as well make it public, so I linked it to WordPress and then social media. Pretty soon there were a lot of people looking in.

Then one day, a few years later I was looking for an ad by Tom McElligott, a copywriter I really liked, and I couldn’t find it. In fact I could barely find any of his ads on the net which was insane. So I thought I’d write something on him, scan a load of his ads, and then it would be on the net. Within a couple of weeks it had got 60,000 views, which was a shock. But a few people had written comments complaining that some of the ads I’d posted as Tom’s were done by a different creative director, Pat Burnham. Then I got an e-mail from Pat.

“Uh, oh, here we go—he’ll tell me how so-and-so wrote this ad or something.” But he didn’t—he just told me how much he enjoyed the article. So I wondered ‘how can I make up for not crediting him? Bingo! I’ll do a mini-interview to right that wrong?’

I’d never done one, but thought ‘how hard can it be?’ It was great to be able to ask someone you admire about all the ins and outs of how they work. So I ended up doing more. At some point people started saying I should do them as podcasts—which I resisted—but then I interviewed Joe Sedelmaier, an amazing director from the States. He said, “I’ll do an interview, but I don’t want to have to write—I’m 84.” So I recorded our three hour conversation and transcribed it. In listening to him talk, he kept swearing, it looked too harsh in text, but funny when you heard it. It made me wonder whether I should put out the recording, it was nicer hearing him talk. Besides, it took me eight hours to transcribe.

There’s a huge amount of history there. Do you think it’s important that there’s a place for this stuff?

I don’t know whether it’s important, but it’s useful. When I first started I couldn’t get my head around how people were so excited about some crappy new way of creating banner ads whilst being so dismissive of ads like British Airways ‘Face’. I’m no tech guy, but to me you can’t compare the two. I just wanted to admit that I liked this or that ad, this or that creative, not many were admitting it at the time, it categorised you as a dinosaur—kind of like coming out of the closet.

Because I started off in bad agencies, I was always trying to work out how to improve—I used to cut out ads and keep scrapbooks of these things. So I had a lot of stuff, it’d been useful for me, so I thought it’d probably be useful for students too. I’d be loath to say it’s important per-se, but I like it—it’s fun to grill people like Frank Lowe or Alan Parker.

30 years from now what adverts from today will be looked back on fondly?

I don’t know. It’s always hard to see in the moment—it takes a while to judge things. People now think advertising in the 70s, 80s or 90s was great, but look back at magazines from the period and you’ll find that most of it was rubbish, it’s just that the bad stuff is no longer talked about or shared, only the good stuff is seen today.

The difference is that advertising had a captive audience back then, so it was a bigger part of the nation’s psyche. Because it had more influence, budgets were bigger, which meant people were paid well. Today, if you’re creative you could be choosing between starting at an ad agency on £17,000 or Apple on £70,000.

“If you feel awkward saying it to another human being don’t say it in an ad.”

Consequently our industry has less of a pick of talent than it used to. There’ll be a knock-on effect, it’ll show up on the streets and screens. But the business is always being reinvented, hopefully some young Turks will turn up and call bullshit—start a revolution where they say, “Fuck boring, patronising crap—let’s make stuff that’s fun, that people like.”

Yeah it does seem that there are constant cycles for these things. Winding this down now as we’ve talked for ages, in a hypothetical situation where you can only watch the same advert repeatedly in all ad breaks for the rest of your life, which advert would you want to watch?

Tough question. Ask me tomorrow and it’d be a different ad—but the two that spring to mind are the Guardian ‘Skinhead’ ad and the Canal Plus scriptwriter ad—where the guy’s in the wardrobe explaining how he got there. I could list 100, but that would break your one ad rule. Which I’ve already done.

Give us one more then…

I really like the Benson and Hedges one where Arthur Daley is a spy; Istanbul by CDP, Ridley Scott.

Going on a bit of an aside, you mentioned Ridley Scott there doing adverts. Is advertising still an area that film directors are still bothered about?

Some, Wes Anderson makes ads, so do the Coen Brothers. But the more interesting question is whether there are those amazing people coming out of advertising into film. There was a period in the 70s where Soho gave Hollywood Alan Parker, Ridley Scott, Hugh Hudson, David Puttnam, Adrian Lynne…

Michael Cimino was an ad guy too wasn’t he?

Yeah. And then John Hughes, he was a copywriter. They wrote ads then went on to make films—blockbuster films, they ruled the 80s. I had role models like Alan Parker—he made it seem possible to graduate from D&AD to the Oscars—I didn’t, you might’ve noticed? But it felt possible, I don’t know if that path is open today?

Who knows? Maybe we’ll get Quote you Happy—the Movie? One last question—have you got any final words of wisdom to impart?

Just do what you like. I run a course at ArtCentre in LA about coming up with ideas within them rather than their computers. The more original stuff is within them, so we explore what they think about a product, category or target group.

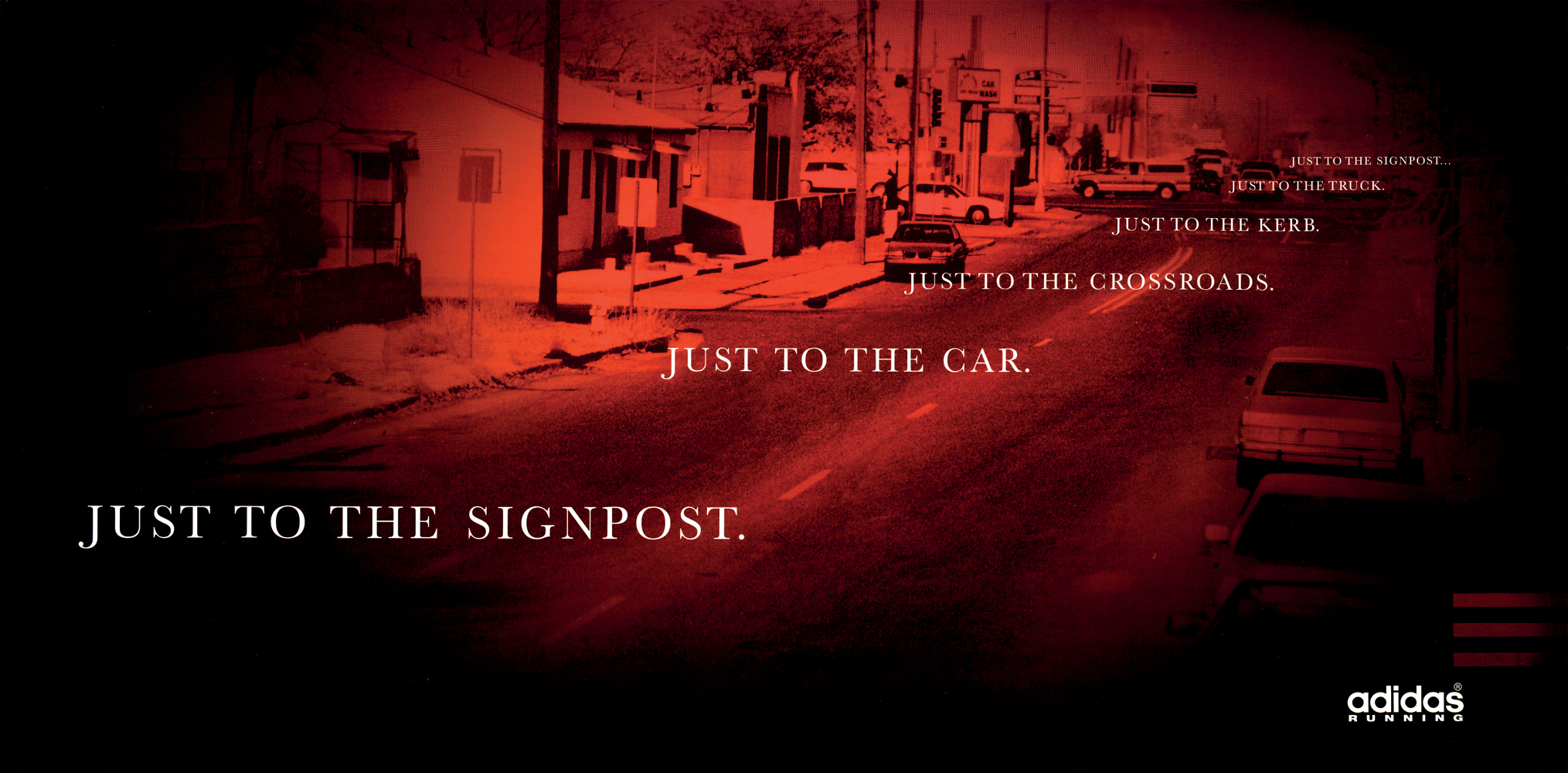

Like that adidas advert you did about running to the next signpost?

That’s a good example. Instead of looking at other ads, I thought, ‘what do I do when I run?’ I thought of that and turned it into an ad. I had no idea whether anyone else did it or would understand it, but they did.

That stuff that’s personal or weird is often more universal than you think.

Exactly. People are uncomfortable sharing personal thoughts, they self-edit it out—but I think that’s where the good stuff is. That kind of thing where people go, ‘I didn’t know other people did that too.’