An Interview with Max Leonard and Henry Iddon: the Creators of the Mountain Style Book

The new book celebrating British outdoor innovation

From super-lightweight Rohan trousers to the hearty insulation of a Mountain Equipment down parka, the United Kingdom has a long history of boundary-pushing outdoor clothing. That said, this innovation has never really been celebrated… until now.

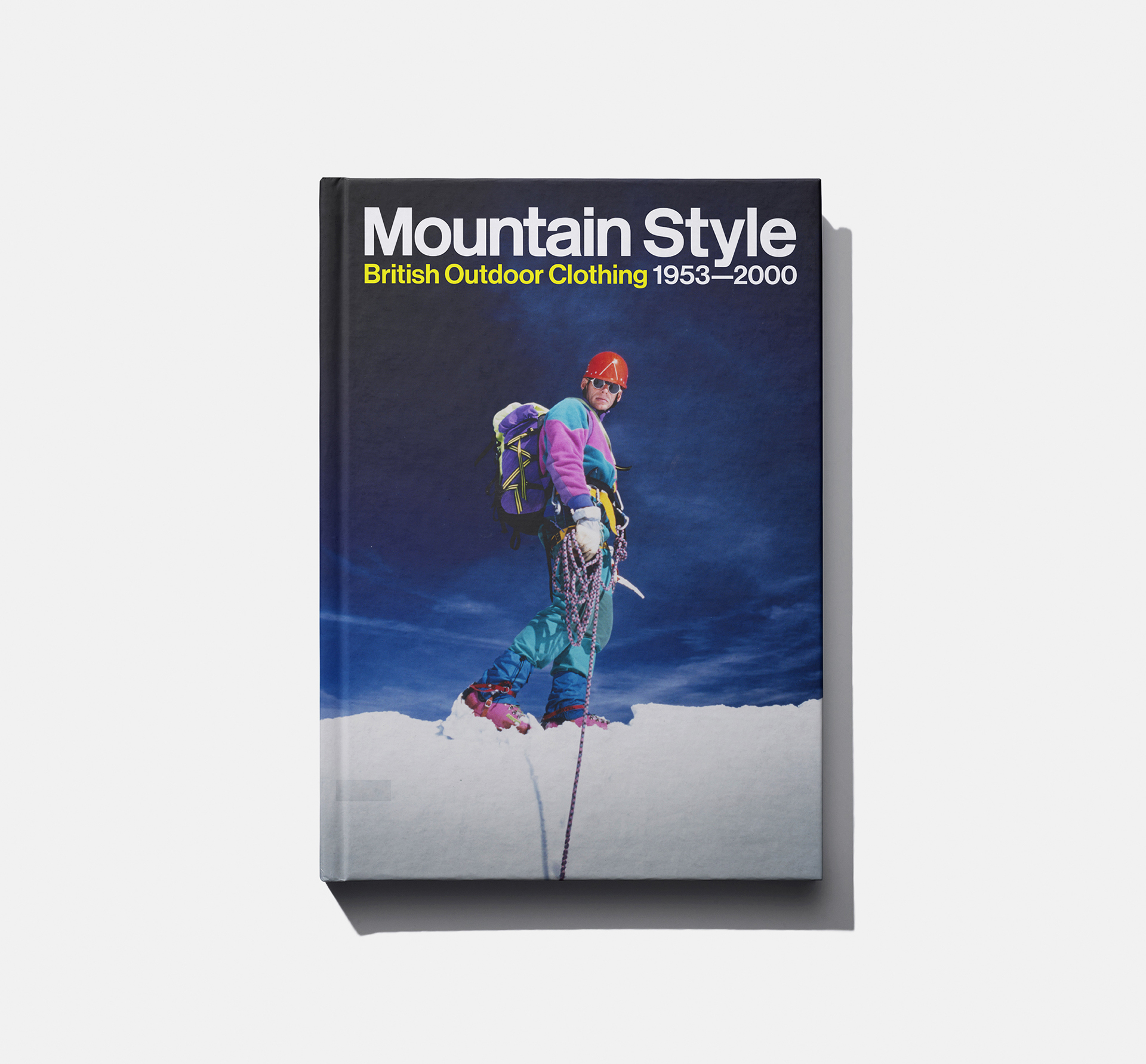

Mountain Style is a seriously hefty tome from Isola Press which traces the rapid evolution of British mountaineering, climbing and hiking clothing which took place in the second half of the 20th century and how a gaggle of mountaineers-turned-clothing-designers transformed outdoor wear from wooly socks and heavy cotton smocks into a multicoloured world of technical fabrics and life-saving details.

Across more than 300 pages, the book combines in-depth interviews with those who were there with a treasure trove of archive imagery and modern-day studio photography to create a fully wide-angle view of the many, many brands that made an impact.

Max Leonard and Henry Iddon were the two men responsible for this fine piece of work. We called them up to find out more…

First off, congratulations on finishing the book. I can’t imagine how much work went into it. How did it come about in the first place? What was the spark that set it off?

Max: I’d been thinking about it since we did a book on the Rough Stuff Fellowship. If you look back in that book at all the photos from the 50s, 60s and 70s, what they’re wearing isn’t what you’d consider to be normal bike clothing these days.

They’re wearing breeches, long socks, brogues, woollen shirts, Ventile and wooly hats—and I just thought that in the same way that the Rough Stuff was a subculture that hadn’t really been documented before, there was all this history of British outdoor stuff. There was something to explore there—and having done archive projects before, I was hopeful that the brands would have archives of their stuff.

But there was a time pressure on it—it was something I was thinking about before Peter Hutchinson of Mountain Equipment passed away a few years ago. And then in the time we’ve been working, other important people have sadly died too.

It’s important to capture this stuff and get this information down before it’s lost.

Max: Yeah—and given that the main bulk of this stuff happened in the 60s and 70s, the founders are of an age now, and when the companies get sold and resold, the archives don’t necessarily get passed on. We talked to the guys from Pertex, and they were telling us how they used to have a brilliant archive, but then when it was sold, it just got binned.

How do you start something like this? It’s fairly all-encompassing, from photographs from brands to studio photography to adverts, there’s a huge mix there. What was the process?

Henry: It was just a case of starting from the beginning really… or finding a beginning. Max had done a talk for me when I was involved in Kendal Mountain Festival, so we chatted and got to know each other then. And then I did some images of the ephemera for the Rough-Stuff book for Max.

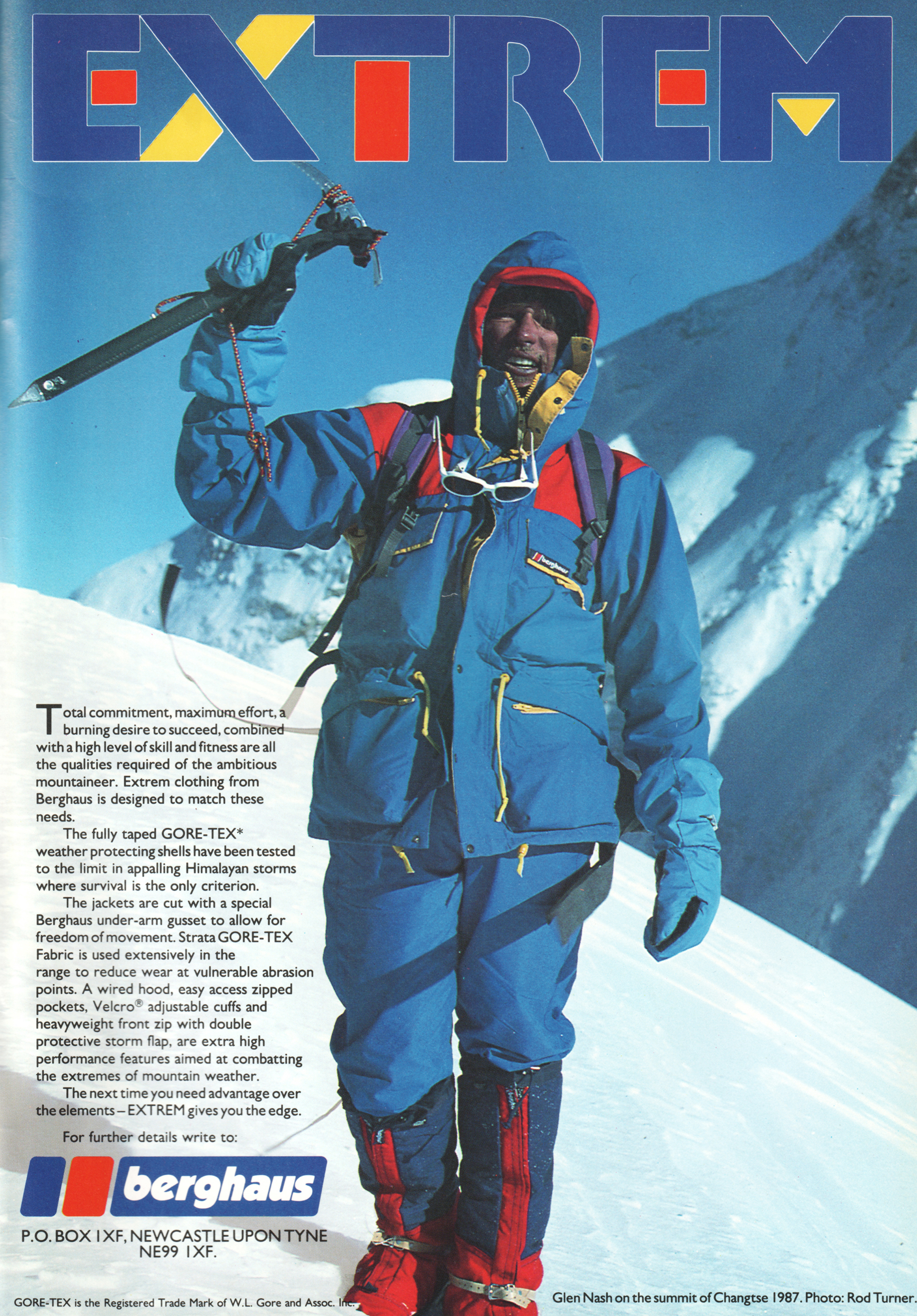

I worked in a gear shop in the 80s back when it exploded—I’ve got a cycling and mountaineering background—so I’ve always been a bit of a gear nerd. So when we chatted about it, it was a dream team in a sense—me being a gear nerd and Max being a writer with interest in heritage and history projects. It was just before lockdown we contacted a couple of the brands—I’d been doing work with Pentland who owned Berghaus—so I spoke to them about the idea. They were the first brand we’d contacted—telling them what we were doing and asking if we could look in their archive, and it just went from there.

Max: We went to brands, we went to mountaineers, we went to photographers… and then Henry had a treasure trove of magazines.

Henry: I’m in the Fylde Mountaineering Club, and I found a big stash of magazines in one of the huts. They’d used the pages to decorate the walls… with these old ads as wallpaper, in a sense. So I had this treasure trove of magazines from 1964 through to the early 70s. And then by chance I spotted a stack of Climber magazine in Kendal’s Oxfam. I also had some Footloose magazines from the early 80s along with Mountain magazines and High magazines. And all these magazines had reviews for clothing and products and the latest releases, which we could then fall back on as source material, so we knew the costs of things and when they were launched.

Max: In our head, we wanted to get a studio shot of the garment, then talk to the founder of the company that had made it, then get some photographs of it being used on the hill, and also some adverts of them from the time… and in quite a few situations we did manage to get all of that. We tried to get as 360 degrees as possible.

It definitely shows. It’s a full view that covers a lot of different brands.

Henry: My father was a very early member of the mountaineering club in the 50s, and I found a tin with his photos in, as well as the negatives which were shot on medium format film. There were ski shots from the Lake District and climbing shots—and they were gold—I doubt there’s much vernacular local climbing club photography from that era in existence. My father was a pharmacist, so I’m guessing he had access to decent equipment and film. Now people take images ubiquitously on phones, but one of the issues we had was finding really good quality images. We could find the expedition stuff, but the vernacular, everyday photographs of people wearing the gear was really difficult.

Quite often the history of a subject like this can be quite prone to exaggeration or embellishment. Brands will often lay claim at how important their gear was—but your book shows what was really worn and what brands really were important.

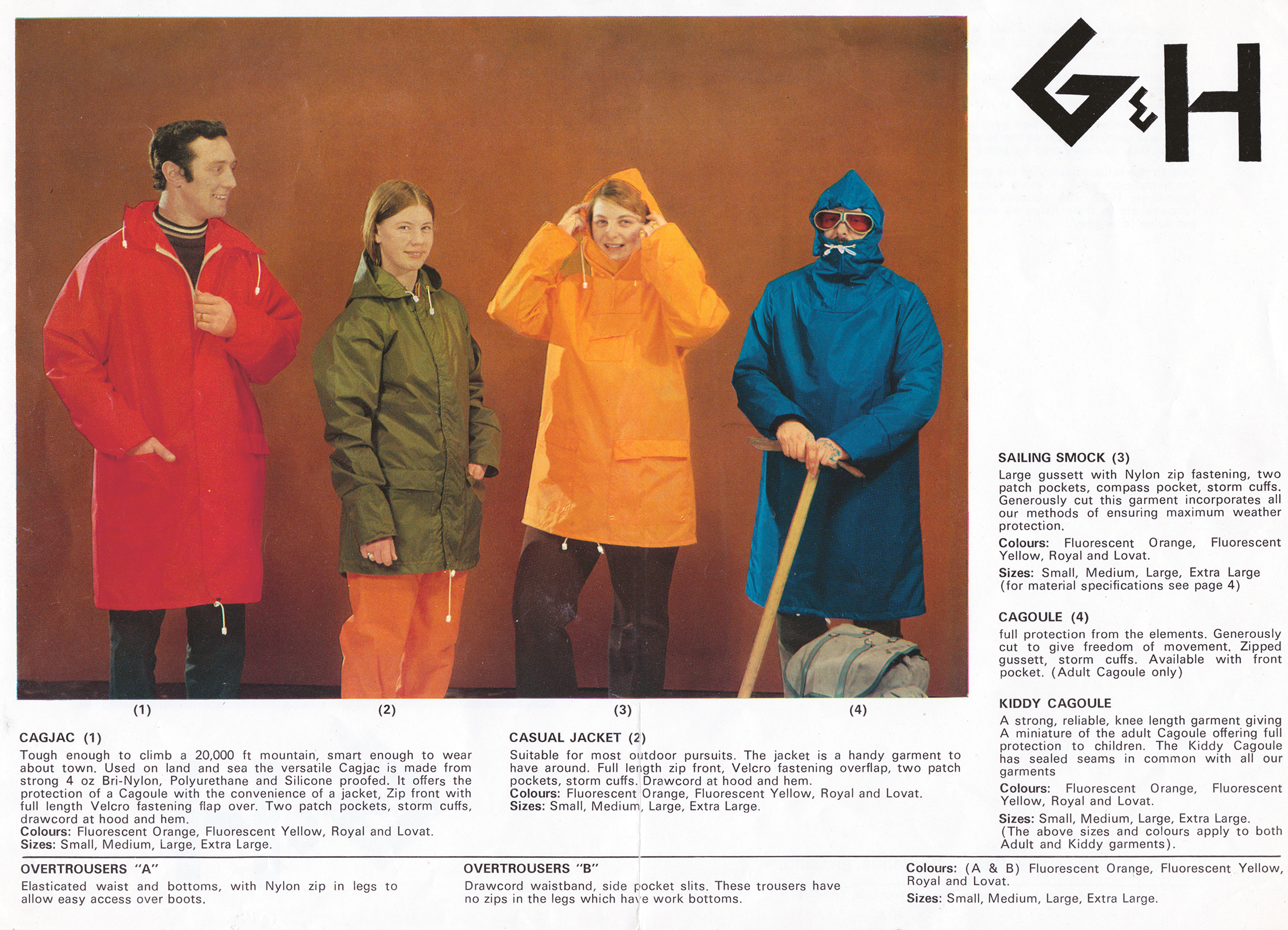

Henry: Yeah—and there was surprisingly little clothing around. In the 60s, 70s and even in the early 80s you wouldn’t really see adverts for clothing—it’d just be tents, sleeping bags and boots. It wasn’t really until the mid 1980s that you started to see more general clothing and leisurewear.

I suppose before the 80s there maybe wasn’t that ‘full technical outfit’ idea there is now, with a layering system. Apart from a jacket, the rest was fairly cobbled together.

Henry: That’s what’s interesting in regards to the gender mix of outdoor clothing. In the 70s cagoules were just shapeless bags—they had to be baggy to let the air circulate—so they weren’t gender specific. If you were a woman outdoors in the 70s, you’d wear a cagoule and thermals. And everyone wore thermals in the 70s because nobody had central heating.

Max: Outdoor clothing was just clothing. People these days observe that the industry doesn’t serve female customers as well as male customers, but that’s really a result of how the technology moved on, how it was pushed on by these big expeditions and male mountaineers either working with manufacturers or setting up companies to make stuff.

One of the big stories is the fabric technology and the improvements there. In the first 10 or 15 years of the book, not much happens—you’ve got cotton and wool, and a bit of nylon comes in with the 1953 Everest expedition—but it’s really only until the mid-70s when nylon gets going and you get the cagoules coming in, but the rest doesn’t change until a little later, when you get the other synthetics, like the base layers which come in via the Helly Hansen Lifa vests.

It feels like there was two things happening at the same time—there’s this wave of young designers with new ideas, and then unawares to that, there’s these factories making new fabrics and using new technology.

Max: The technology is completely bound up in the story of the different companies. It’s why so many brands were based in the North West and Yorkshire—because of the historic textile industry and all of the mills. Even in the early 80s, they’d get their fabric woven 20 miles away. It wasn’t like now when everyone depends on global supply chains.

Wasn’t that why Rohan was in Yorkshire? They were looking for modern lightweight fabrics.

Henry: They were based in Skipton, and they didn’t make their own stuff—they outsourced it all. Craghoppers made breeches for them. By having things locally sourced, it meant they could make prototypes easily. If someone was going on an expedition and they needed a bit of kit, they could go down the road to get the fabric, and then have a machinist knock it up.

Whereas now, if you’re a UK-based company and all of your stuff is made in China, you’d spend a fortune by courier sending it out, and then it’d probably need some tweaks, but back then the development would be so much quicker.

What was going on culturally that led to the start of all these brands and all this innovation in the UK?

Henry: During the 1970s, British mountaineering and alpinism was at the cutting edge—the likes of Joe Tasker, Pete Boardman, Brian Hall and Rab Carrington started pushing this fast and light idea, so it wasn’t these huge siege expeditions with sherpas and cooks. It was about being super lightweight and climbing the mountain with the best style—so with that you needed good quality equipment that your life could depend on. They were doing hard routes on big mountains where there was a lot of objective danger—the longer you were there the more chance of a serac or a rock landing on your head—so you needed to be quick.

Max: That was the big factor that pushed it on, and then we already had the textile history of and also we had this imperial attitude of wanting to go and climb things. You can even talk about that with Everest in 1953—it was Britain projecting its power. And then the weather is an important factor, because the UK climate is pretty exceptional. All these things pushed it on—and then a group of mountaineers put it all together.

How did this stuff differ from the American outdoor gear of the day? Were there differences in details or approach?

Henry: One of the key things over here is the weather. If you’re in the States—unless you’re in the Pacific Northwest where it never stops raining—then you’ve got quite settled weather patterns. And it’s the same with Europe. But we’ve got a maritime climate, and that made a huge difference to the way that companies develop their equipment—and that’s why the cagoule was so big here.

Max: When they first made the material that would become GORE-TEX, they didn’t know what to use it for—cable insulation and then cookware were two applications. I think one of the reasons why they came over here so early on was because of the weather, and the reputation of the climbers.

Henry: One thing that happened in the States was that Eddie Bauer supplied the American air-force with insulated jackets—and in theory, they’d have been white label, but he insisted he put his brand in them. So when everyone left the military they knew what jackets they’d worn—so when they started going out hiking, they wanted an Eddie Bauer because that’d kept them warm at 30,000 feet.

And that links in with the story of the down-duvet, which was invented by George Finch for the early Everest expeditions. And then the down-duvets worn on Everest in ‘53 were French, because there were no real UK manufacturers of down jackets, even though Finch was making them in the 20s, because over here, they’d just get soggy.

I suppose that’s why you get a brand like Páramo. The technology there feels very specific to our damp, mild climate.

Max: Too often it’s easy to look at British innovation as guys tinkering in a shed, or these old eccentrics, but the fabric technology that’s in a Páramo jacket or a Buffalo smock is not to be sniffed at. I think one of the things we were trying to do with the book was to claim some sort of history for the UK stuff—to highlight it a bit is to push back on the idea that it was just these crackpot inventors, and that they were actually world-beating ideas.

“Too often it’s easy to look at British innovation as guys tinkering in a shed, or these old eccentrics, but the fabric technology that’s in a Paramo jacket or a Buffalo smock is not to be sniffed at.”

Henry: The Americans are very good at eulogising their history, whereas the British are quite understated by nature, so we don’t celebrate our history the same—maybe because we’ve got so much of it that we take it for granted. But there’s Bonnington and Whillans and Haskett Smith, the Abraham brothers climbing in the Lakes, or Cecil Slingsby exploring Norway or Leslie Stephen and The Playground of Europe. We’ve got a massive mountaineering history, but we don’t make a song and dance about it.

I feel like it almost needs something like your book to tie it all together. Whereas each brand maybe talks about their own history a little now, your book looks at the whole picture.

Max: The interesting thing was that at least until the late 80s, the brands really stayed in their lane. Berghaus did shell garments, Rab and Mountain Equipment did down insulation—there was room for different people to do different things, whereas now every brand does everything and they’re all competing across the whole range of products. But even now, it’s a very small, very friendly industry.

It feels like there was a real boom, and then by the late 90s there’s this shift where either the companies get sold or they move their production out of Britain and start producing more everyday clothing. What was going on then?

Max: I think the story that we saw was that in the 80s with the explosion of the popularity for outdoor wear for the more general population—and I’m not talking about the raves and the terraces and the subculture stuff, but outdoor wear moved into leisurewear and travel, becoming a bit more of a fixture on the high street and it became a bit more fashion-influenced. Fleece came in in the early 80s and that definitely opened it up to a wider audience. I think a lot of the brands overextended—their operations got too big to maintain, and people made bad decisions or got themselves in financial trouble.

One of the stories we saw too was that by the mid-90s a lot of the founders were getting towards retirement age and it was time for them to move on—and that’s when it all got corporatised.

That makes sense. Once the person who had the wild ideas goes, and you’re often left with numbers-obsessed people who just want to sell grey jackets to the high street, things get dull fast.

Henry: They were also tough times. The economy ebbed and flowed, and that impacted them. Looking at the magazines, in the 80s you can see it had a boom. Sometimes in just one issue of a magazine you’d see three or four full page adverts for Mountain Equipment, and then you’d see in the back in the small ads there’d be outdoor centres looking for staff, which indicated the size of the industry at that time. You can see all that growth, but then by the 90s, the magazines did become thinner.

I know a lot of the brands featured are still going at a big level, but are there any new, young British outdoor brands coming along that are kind of doing the job they did, 40 years ago? Is there still scope for that to happen the same way?

Max: I think the boundaries of innovation are much more difficult now. Going from cotton to nylon to breathable waterproof systems, or wool to fleece, you’re making a huge leap in performance. You could improve something by 500% in just a couple of years and make real big developments. But now everyone has access to the same factories and innovation is much slower. What can you do that is going to be 500% better than the latest GORE-TEX? I think the room for anyone to be making those giant leaps isn’t there.

Looking at the book, you can see that in the 90s a few new things happened. Paramo came out with an eco approach and a whole new system—and that was genuine innovation. And then Montane was another brand from the 90s, and you don’t really see it in the book, but they started moving towards that very lightweight, multi-discipline stuff that they do now.

And then there’s PHD, which was set up by Peter Hutchinson after he left Mountain Equipment. By all accounts, he got frustrated with being at Mountain Equipment once it was bought—he just wanted to make the best gear, no matter what the price. So PHD was just about keeping it small and hand making for individuals.

But that era in the 70s and 80s you could make really big differences, whereas now it’s a lot more incremental.

Henry: In the early days anyone could buy GORE-TEX—so you could be some small brand that made your own GORE-TEX jackets, but now you’ve got to be licensed and pass their stringent tests. And you couldn’t buy a bonding machine to heat-weld the seams—that would cost a lot of money.

Something new will come along. There’ll be a new activity that the current clothing doesn’t work for, and a new brand will crop up… like the Dryrobe. It’s easy to slate the Dryrobe, but that’s a new functional design that I don’t remember seeing 15 years ago.

Max: That’s a good point. It’s thinking outside the box. It’s just pile—like a Buffalo—but it’s carved its own new thing there, and hit a need. And that’s where you make the difference now.

Rounding this off now—with both of you spending so much time looking at old outdoor gear, do you have a favourite garment? Is there something that sums up the attitude or ethos or British outdoor design?

Henry: I think we’ve both got favourite garments. I suppose the cagoule is quintessential—the full-length zip Berghaus or Mountain Equipment walkers jacket.

Max: The amount of advertising you see in the 70s of scores of tiny brands jumping on the bandwagon making PU nylon cagoules because by that point it’s cheap and easy enough to do—that was quite interesting. But in terms of favourite stuff, we talked about Rohan and how that’s still around—but I think we were blown away with how innovative and disruptive it was when it started in the mid-70s.

I think one of our favourite jackets was the Windlord, which was a real mountaineering jacket they made which was worn by Peter Habeler on Everest in ‘78 when he climbed it with Messner. It’s this incredible blue—with very tightly woven cotton on one side, with nylon on the other side—designed to keep ice off.

It’s not even all that valued—no one’s collecting them so it’s not like it’s going to be super expensive, but that is one of the quintessential pieces for me in terms of summing up how the brands were working with mountaineers, and how the mountaineers were pushing what they were doing. The brands were making things that were functional, performed really well and looked fantastic.