An Interview with Graham Fink

An extensive natter with the creative polymath

Graham Fink is what some people might call a Renaissance man. Not content with creating some of the most memorable adverts of the last 40 years—making faces for British Airways and shedding blood for Playstation—he’s also directed music videos, held countless photo exhibitions and even found time to befriend a couple of robots.

And that’s before we mention the software he helped develop to allow him to draw using his eyes, his recent course on creative thinking and his new-found dedication to the classical guitar.

But whereas most people with his experience would be quick to tout themselves as experts, Graham has retained a beginner’s curiosity—ceaseless searching for new ideas. We pestered him via video phone to find out more…

What do you get up to these days? You were working over in China for a while, weren’t you?

Yeah, I was in China for seven years. I was Chief Creative Officer for Ogilvy China, mainly running the Shanghai and Beijing offices, and then I took this job in Seattle, with a company called This Place that designs websites and apps—I did that for a year—and part of the plan was to do something with them in New York, but then obviously Covid came along, so that hasn’t happened yet.

I suppose like lots of people everything’s all up in the air. I’ve been back in the UK since just before the pandemic started, and it’s been great. I still do little bits of advertising, for various people—whether they’re friends, or interesting brands—I like to find interesting problems to work on. I also do a lot of my art—I’m still doing my eye drawings, and I’m doing a new exhibition of paintings on postcards, and then I’ve been doing some design work. And at the same time I’ve been trying to learn classical guitar… which is difficult.

I can imagine. Are you learning from scratch, or could you already play a bit?

When I was ten my dad bought me a guitar and I had some lessons, and I kept that going for a bit—until I got my first job in advertising. Then I just stopped—when you work in advertising, you have no time for anything else. But when I was in Seattle, I walked into a guitar store, and thought that perhaps I could get a good teacher and relearn. I found one, but unfortunately, it didn’t all come flooding back. Three or four months in, my fingers were still really painful and I’d forgotten how to read music. All the progress I’d made before was very slow in coming back.

But because of the pandemic I’ve had all this time to spend at home, and really get the practice in, and I thought, “What I really need is the world’s greatest guitar teacher.” So I found this guy online—and the way he was talking, and the way he was moving his fingers was so unique. He was called Eliot Fisk—and it turned out he was Segovia’s last pupil. We started exchanging emails, and eventually I said, “I’ll level with you, I can’t really play the guitar, but I’d love it if you could teach me.” And we’ve actually had a lesson every month for the last year. He’s fantastic—not only is one of the world’s greatest guitarists, but he’s a great teacher.

And that’s kind of the way I’ve always worked. I think that whatever you do, you should always try to work with the very best people.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Is it important to keep learning new things? It’s easy to shut off once you leave school.

Absolutely. It’s a real philosophy of mine that you should try and get good at as many things as possible—to stay curious and get outside of the things that you’re naturally good at. When I’m in a bookshop, I always go to the art and photography section first, but then before I leave I’ll go randomly to one other section and I’ll pick up a book. It might be a book about engines or cogs or something, and I might just read a page. And it’s interesting—because if you do that enough you can often link these things back to what you’re working on, and it gives you really interesting solutions—looking at things in new ways.

Approaching it from a different angle?

Exactly. If we’re all reading the same stuff, looking at the same blogs, watching the same news and listening to the same friends, we all end up thinking the same. You only need to look at the stuff around you to see that so much is the same. We’ve been doing the same thing over and over again, and we’re never going to come up with anything interesting or different if we keep doing it.

Was it Einstein who said that the first form of madness was to keep doing the same thing and expect different results? I think it’s good to try and throw a few spanners into an engine that’s running well. Can we mess it up a bit? Just to see what happens, create a bit of mischief and have fun. That’s something I’ve always believed in.

Is that hard sometimes? When things are comfortable and working well, it’s not easy to consciously go against that. Have you got to push past that a bit?

I think you do. I’m a big David Bowie fan, and what I like about him was that he was constantly changing. If you look at what was perhaps his greatest era, when he was Ziggy Stardust, he only did that for a year, and then he decided to kill him off on the last night of the tour at the Hammersmith Odeon. He didn’t even tell his band—he just said at the end, “This is the last time we’re ever going to play.” And that was it. And I love the idea that he was so successful, and sold so many records, and then he decided, “Okay, enough of this, it’s all going brilliantly,” and he decided to kill him off. I think it takes such balls to do that. Most of us, when we get a winning formula, we hang onto it. We’re grasping it with white knuckles, milking it for everything it’s worth.

Definitely. A lot of great things often overstay their welcome, to the point they become watered down and lose the spark that made them great in the first place.

I think a lot of artists come up with a winning formula for something, and often that’s the thing that breaks through—when they start to sell work. And then they’ve got to keep reproducing that, time and time again. But you don’t want to be a slave—you’ve got to do what you really feel, and be true to yourself, and the minute you try to do what everybody wants you to do, that’s when you’re in trouble.

Have you had that? You’ve had some really successful advertising campaigns—have clients wanted you to almost ‘play the hits’ before?

A lot, yeah. And for a client, they get a winning formula, and everything’s going great, the last thing they want to do is change it. But it gets to a point when people have had enough, and they want something different. The world changes, and the mood changes—I mean look, in the last 18 months the world has changed beyond a way anyone could have ever predicted. We read all these predictions at the beginning of every year, and no one predicted what was coming—well… maybe Bill Gates did?

“I think that whatever you do, you should always try to work with the very best people.”

And it’s amazing how we learn to adapt. Even my dad is now posting his paintings everyday on Instagram, and answering people’s comments, which is great. He’s 86, and he’s set himself up on Zoom. He’s a butler, so he’s been doing butler training, and talking to students—which is extraordinary. So we really are adaptive creatures—everything changes and we learn to adapt.

You seem particularly good at adapting. I’m completely stuck in the past, but you’re constantly working with new technology, maybe in a similar way to how David Hockney does. Have you always been like that?

I think so, yeah. I’ve always wanted to be this explorer. Hockney is a great example. I went to his retrospective at the Tate, and it was extraordinary. There were all these different rooms—drawings, paintings, silk-screens, polaroids, and then these drawings on his iPad, blown up huge. What an extraordinary artist—he’s just trying out all this new stuff. He’s just curious, and I think that’s what we should all be.

I’m not a techie, but I really love playing around with technology. I’m doing some work with robots at the moment. There’s Sophia, who’s very interesting, and then there’s a new robot called AI-Da, and she’s the first humanoid robot artist. She’s doing this art where she’s taking photographs of herself in the mirror, and then printing them out as an inkjet print and then drawing over the top. She’s kind of creating these self portraits, but what is interesting is that there’s no real self, if you see what I mean? She’s not sentient—she’s a machine—and yet she’s drawing these self portraits. It raises all sorts of interesting questions about creativity and art. Do you need to be human in order to be creative? She’s certainly doing stuff that’s new, original, interesting and meaningful—it has a place in art history.

People are saying, “Where is the art?” Is it the person who came up with her? Is it the coders? Is it her? Is it the algorithm? It’s a very interesting question, and I love the fact that it’s challenging our views. For me, it doesn’t really matter about the answer, I find the debate more interesting—everyone is going to have all sorts of different opinions—and I love that. It makes the world more interesting—it’s kind of beyond our understanding. So many of us walk around feeling like we know everything, but we know fuck all.

It confuses people when things don’t fit easily into a category. As robots become more creative, are humans becoming more robotic? There seems to be an almost digital, ‘on/off’ mindset with people sometimes.

I was reading somewhere that more and more teenagers who play Fortnite would rather be on there with their mates than meet up with them in real life. And rather than play the game they just like to hang out. So what does that tell you about the real world?

This ‘metaverse’ is a very interesting space. It’s going to be wild—putting on a headset and just wandering around a 3D internet, where we do all our shopping and have all our meetings. And once we find that it’s much easier to do that then go outside your house in the rain, maybe we’re just going to become more and more interested in sitting at home.

You talked before about pushing past the comfort zone, will there be an element of that with this new technology? It might make things easier, but will it be a fulfilling way to live?

I don’t know. It depends on what you think is fulfilling. And again, I think everyone has slightly different views on that. Perhaps to us it seems a bit sad and lonely. Maybe doing it for a week would be exciting—to jump into the metaverse and do all these amazing things, but I think after a bit we’d think, “I just really want to go and meet my mates for a drink.” But that’s just me, maybe not everybody thinks like this. Different cultures have different views, and things mean different things.

In China, the thinking is very different to Western thinking. When I first went there I thought, ‘this is going to be quite easy—I’ll bring in some friends of mine from the UK who have done amazing work and we can come up with amazing stuff, and just translate it all into Chinese.’ But it doesn’t actually work like that. You come up with stuff, but when you test it out on the Chinese audience, they say it’s too Western—it doesn’t have a ‘Chinese-ness’ about it. And it took me a long time to understand what they meant by that, but the semiotic codes are very different there—the things they respond to and the things they see.

I look at stuff like Chinese art and calligraphy and think it’s fantastic, but to them, they’re surrounded by it—it’s like if they came to London they’d think red buses and taxis are amazing, because it’d be new and interesting to them. But to us, it’s boring.

Yeah, it’s cliched.

There was a great story I heard about a tribe in the Amazon. They had an event that happened once a year, where the two villages came together and played what we might describe as something similar to a game of basketball. Only in this version of basketball, the ball is really, really heavy—you can hardly lift it.

Anyway, to be picked for your village side is a huge, huge honour—people spend their whole lives wanting to be in that team. They play this game, and the captain of the winning team gets eaten. To be eaten is the ultimate accolade, but we’d be thinking, “Hey lads, let’s slow down a bit.” So what works in one place doesn’t necessarily work in another, and explore them as much as you can, because it gives you new and fresh ideas.

Does that come back to that thing of everyone thinking they’re an expert? It’s better to be open to new things, rather than thinking you know best.

Yeah, there’s that great quote, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.” I like being a beginner, because when you’re a beginner you try all these new things. You’re very naive. You do stuff you’re not meant to do, because you don’t know any better. And what tends to happen is that then you come up with new interesting things that haven’t been done before, whereas when you’re an expert, you say, “You don’t want to do it like that, because that’s not the way to do it.” You’re sort of limiting your choices.

When I was a young art director, I was good at drawing with my right hand—my right hand had become an expert, so I started drawing with my left. My left hand was certainly a beginner, with nowhere near the expertise of my right hand, and yet interesting things would happen. You’d start to trigger a different bit in your brain, and you wouldn’t draw stuff quite as well, but the little mistakes often give you new ideas.

You mentioned before how your dad was a butler, but also that he painted. Did you grow up in a creative household?

Yeah, my mum was very creative. She was always doing interesting things. My dad had done some evening classes for painting when I was about ten, and I’d never seen him paint or draw since, but after my mum died five years ago I got him some art lessons. And it just turned out he’s a natural. It was a hidden talent, and I wonder what would have happened if he hadn’t gone into the navy and had his butler training.

But then he’s an amazing butler too. His attention to detail is really second to none, and I really picked that up, because as an art director in advertising, how everything looks is crucial, and by literally moving something a millimetre, it can make a huge difference. And I like that. It’s almost imperceptible, yet it’s perceptible. It’s something intuitive which you pick up.

What works and what doesn’t work are often very close. When did you decide you wanted to do something creative? Was that something people did when you were growing up?

The careers officer at school was clueless, they didn’t know anything about all this stuff—they certainly didn’t know about advertising. They just tried to dissuade me. They told me no one makes a living as an artist. But for me it was between the Navy and going to art school, and luckily I chose art school.

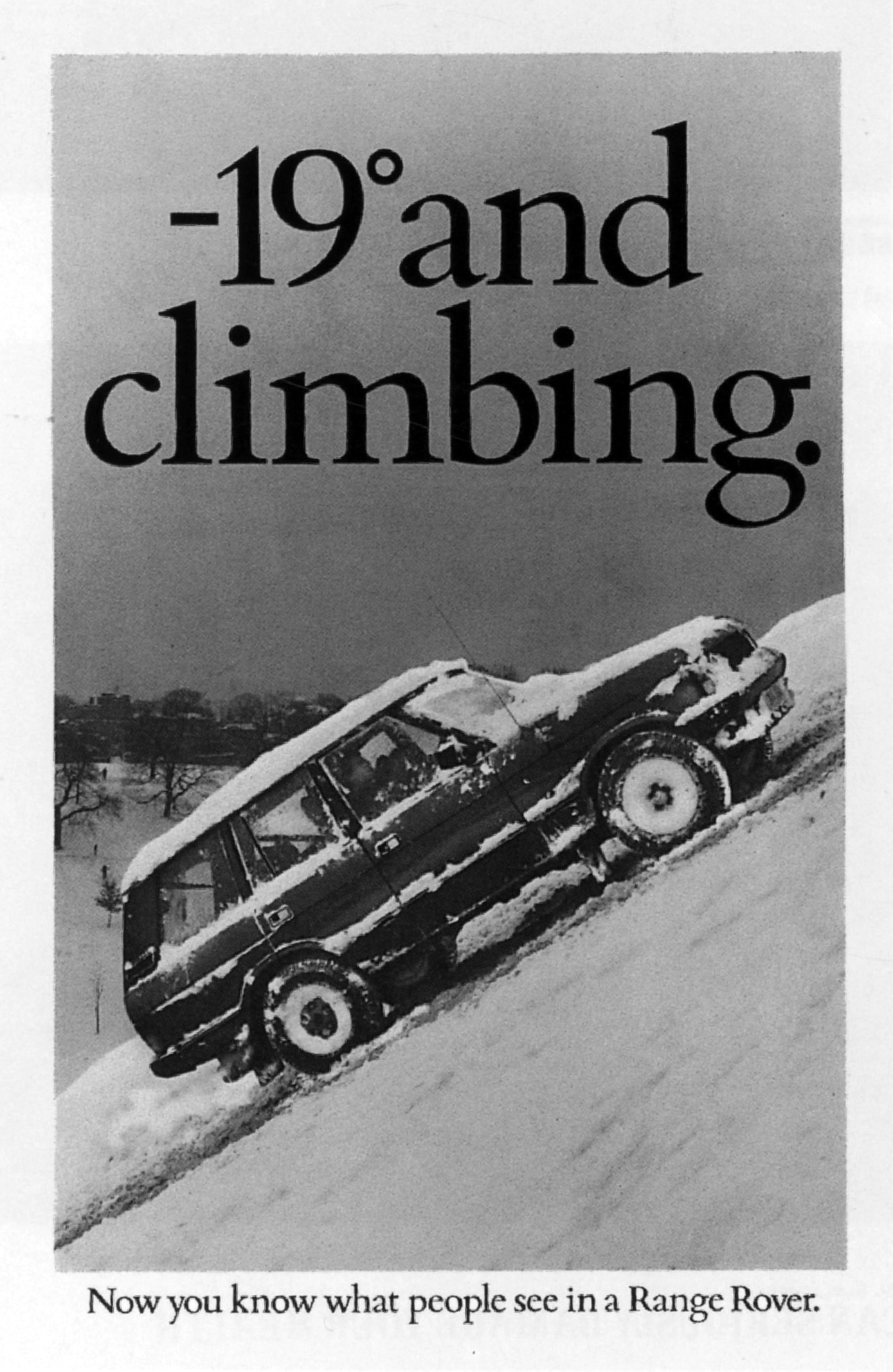

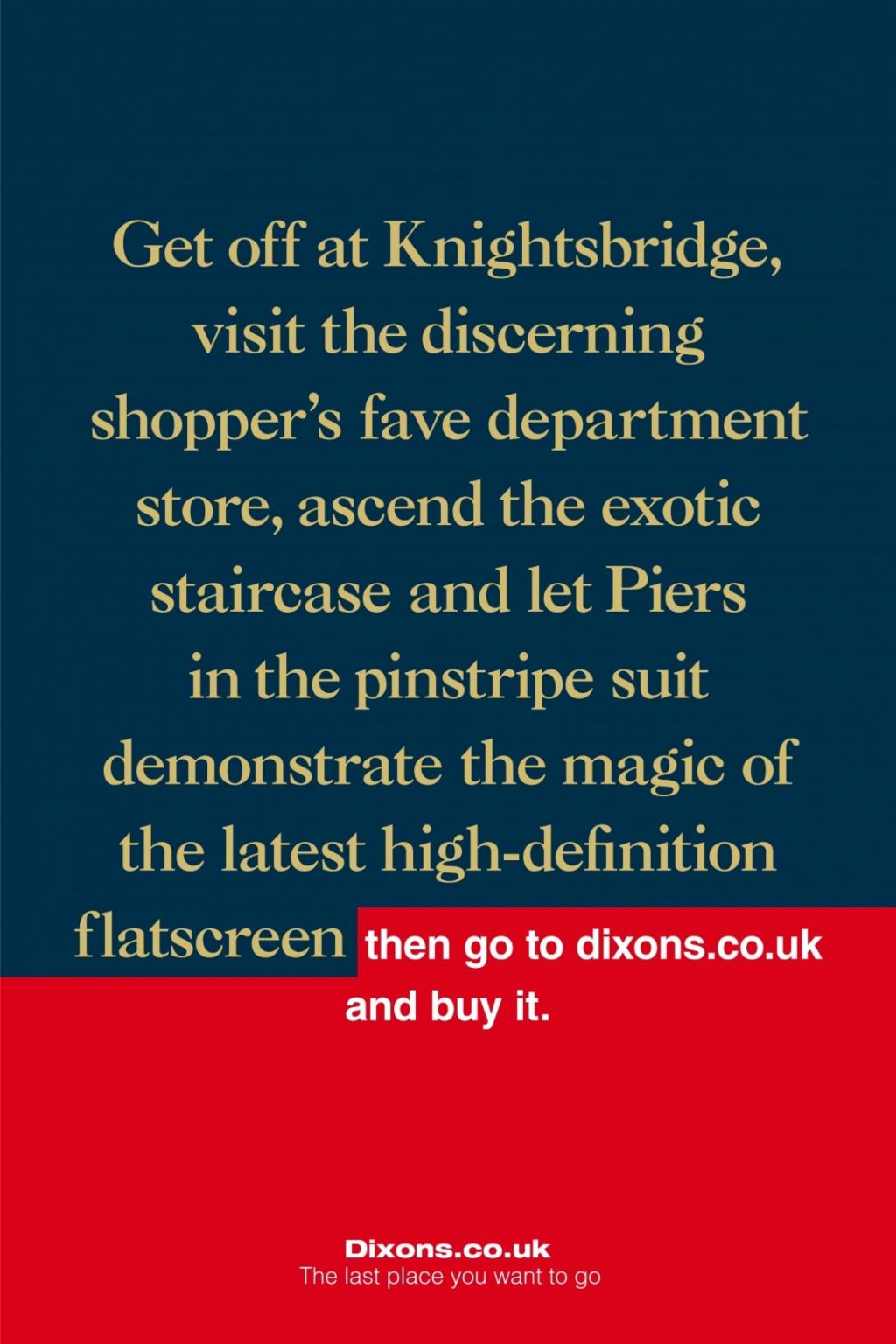

I was really lucky because I had a brilliant tutor, this guy John Gillard, who had a background in advertising. And when he told me about advertising, it sounded amazing. It was photography, it was illustration, it was film, it was music, it was design, it was layout, it was ideas… I thought, “This is amazing… and you get paid to do this?” So that’s why I got into advertising. I always saw it as a form of art, and although I know you’re doing work for brands, I always tried to use it as a way of expressing myself. I always used it to try and do interesting things, and express myself.

What was the drive behind your advertising stuff? Was it, “I want to help this brand sell more stuff”? Was it, “I want to get across this message”? Or was it just wanting to make something that looked cool?

I think it changed over the years. When I first started, it was just an exciting opportunity to do great work. And I’ve always had that—to try and do great work that stands out from everything else—work that gets talked about. If you go into a bar and you hear other people on a different table talking about something you’ve done, or if they’re whistling your song… that’s when you know when you’ve had a huge impact, and it’s become part of the culture.

What was the first thing you made that did that?

I did an ad for Ariston—the washing machines and cookers—and I remember someone in a bar talking about it. It was a visual trick, and this guy was trying to explain it to his mates. And that was quite funny.

You were saying how the drive changed over the years? How did it change from just wanting to do good work?

I’ve always wanted to do good work, but I think when you take on more responsibility—when you’re a Creative Director and a client comes to you with a real business problem—then obviously that becomes important, as well as doing great work. When you’re a Junior Art Director, you’re just there having fun, doing great work—you don’t really think about whether it’s going to sell more or not, or at least I didn’t. But I always tried to do something different.

The creative course I just launched is called Fink Different is about trying to think differently, with everything that you do. It’s exactly that. If everyone’s doing one thing, do the opposite.

Within reason though, surely? Are there limits?

There are. You’re not saying for people to jump off a building because no one else does, but then again, you sort of are. You’re trying to get people into a different mode of how they look at something. So even if you don’t jump off the top of a building, you could imagine doing it, and you could imagine what might happen—and use that as a device to have interesting creative thoughts.

What happens if you don’t just fall? What happens if something is unique about you, and you grew wings and flew? And you might think that’s a stupid idea, but often that’s where a lot of good ideas start—they start from a really stupid conversation. But the reason most people don’t have these stupid conversations is that they’re fearful, and they’re frightened that people are going to look at them and say, “That’s really stupid.” So my job when I’m working with people is to try and create a safe environment—to say, “Look, you can come up with the most stupid things, because you may say something really stupid that gives someone else an idea.” I like combining two opposites.

What do you mean by that?

If you were going to open a restaurant, most people would think about what food they were going to sell, but what if you combine that with jumping out of an aeroplane? What about if you said, “Okay, the restaurant is going to appear in mid-air, and the sky-divers are going to eat there on the way down.” And you might think that’s ridiculous, but I’m sure if you worked on those two areas you’d come up with a really interesting idea for a different type of restaurant. It might not be in the air, but it might change the way you think about having a restaurant here on the ground.

“When you’re a beginner you try all these new things. You do stuff you’re not meant to do, because you don’t know any better.”

I like taking two completely opposite things that wouldn’t ever go together, and say, “Let’s just try and run with this for a bit, and see what happens.” Even if you just gave that idea ten minutes, I’m sure you’d come up with something really interesting. People are hesitant to start with, but once they get over it, they start to realise they’re actually having quite a lot of fun. If you had an hour of that you’d come up with all sorts of crazy ideas, and the room would be full of interesting stuff. From that, you’d be setting the foundations for something really new and fresh.

But too often we go into something as an expert. That’s one way of doing it, but if everyone’s doing it like that, you’re all going to come up with similar stuff. That’s why when you turn on the TV there’s no adverts that really stand out. I think most of it is dreadful. And I’m not saying it was great 20 years ago—there was still a lot of terrible stuff then—but it just depresses me a bit. I see less and less unusual, really interesting stuff.

There’s a lot of dull adverts out there.

I went to the Photo London fair last week, and I was looking for new photography that was different—something that stood out. Sure, you’ve got some very old stuff like the Robert Capa stuff, which is amazing, but what about the really new, emerging photography? I probably spent six hours there, scrutinising everything, but I left really disappointed. I think there’s a huge opportunity to do something new, but why aren’t we doing that?

Is it a lack of confidence? Or is there too much money involved in things? It’s hard to try something different when there’s a lot of money on the line.

I’m not sure it’s just one thing. There are of course some things that do stand out, but they’re very few. Most of it is just copies or some kind of bad transposition of something that’s already been done. You can walk around so many art fairs and say, “Well, that was taken from a Warhol. That was taken from a Jeff Koons. That was taken from a Tracy Emin.” You can see all the influences. And there’s nothing wrong with being influenced by something, but you need to add a bit of your own unique personality to make something really stand out. What makes a great photograph? Maybe you don’t know what it is, but it’s something that really strikes you when you first look at it. There’s something about it that you can’t perhaps explain, and you go, “That’s great, I really like it.” And then you look at it again, and you start to see things in it—things that maybe remind you of things in your past or your childhood, and really resonate with you. I think if a piece of art is really good, it’s going to be something that you keep finding something new in. I want something on my wall that I see something different in every time I look at it—something that still remains fresh.

That’s not an easy thing to achieve. Everything’s subjective too. One thing might mean something to me, and nothing to you.

I like the mystery. It’s good to have mystery—where you don’t understand all the answers. That keeps you questioning.

Maybe that’s why people like David Lynch. It’s nice to not know what his films are really about. But more often than not it feels like on TV or films everything has to be explained, or wrapped up.

Like you, I like watching those David Lynch movies and thinking what they mean. You watch them again, and you’ll see something different in them the second time. I always like watching films twice because often what happens in a movie is there’s a big twist at the end—you don’t see it coming. But when you watch it again, you know the story, so you can sort of relax. You’re looking for different things. You see so much more the second time around.

What sort of things inspire you? Do you watch much TV?

I’ve been watching Drive to Survive. It’s fascinating. It’s about Formula 1, but it’s not—It’s all about the human relationships and the politics.

It’s a crazy industry.

I was amazed they were allowed to show some of the things that they did. I also watched The Last Dance, and that was just astonishing. The mentality of Michael Jordan—what he goes through and how he fights back—is just incredible. Like Drive to Survive, it’s about being obsessive, but it comes across even more in The Last Dance. To be a great, great champion like that, you have to have that absolute obsessiveness about everything, right down to the last detail.

Take the Olympics—when Michael Phelps won all those gold medals, there was one race where he and a competitor both touched the plate at the end, and it looked like it was at the same time, but they were split by something like a thousandth of a second. Which, when you come down to it, it’s the fingernail. You’re swimming 100 metres, and when you win you literally win because your fingernail is a fraction longer than the guy who comes second.

You’d be annoyed if you trimmed them.

It’s extraordinary. And that’s what it’s all about—it’s about that fingernail. I think there’s a great lesson there, for whatever you do—it’s about the fingernail.